Editor’s Note: Rachel Simmons is the co-founder of Girls Leadership Institute and the author of “Odd Girl Out: The Hidden Culture of Aggression in Girls.” Follow her on Twitter @racheljsimmons

Story highlights

Rachel Simmons: Some of Steubenville rape victim's girlfriends testified against her

She says 'rape culture' affects girl behavior too, silences them when another girl is in trouble

She says girls absorb message from early age: be sexy, compete for boys' attention

Simmons: Labeling others "slut" allows girls to withhold help. They must be taught different

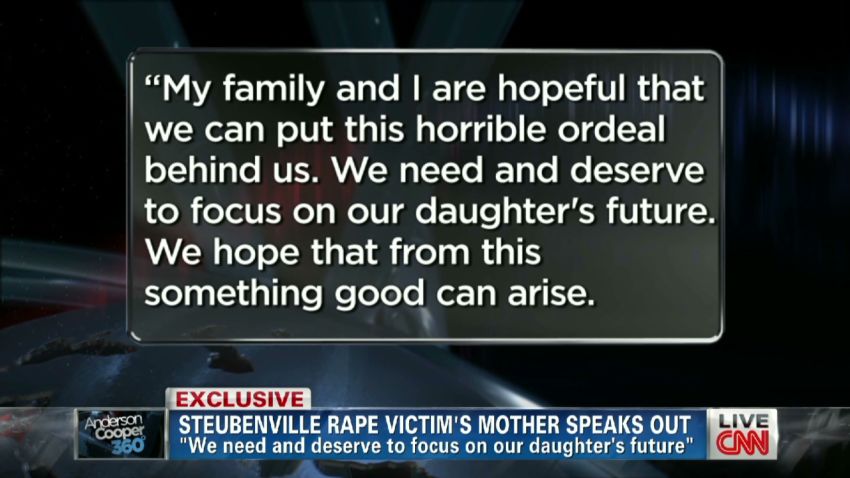

Is anyone else wondering why the Steubenville, Ohio rape victim’s two best friends testified against her? With this week’s arrest of two other girls who “menaced” the teen victim on Facebook and Twitter, we have the beginnings of an answer.

Rape culture is not only the province of boys. The often hidden culture of girl cruelty can discourage accusers from coming forward and punish them viciously once they do. This week, two teenage boys were found guilty of raping a 16-year-old classmate while she was apparently drunk and passed out during a night of parties last August. Everyone who was there and said nothing that night was complicit; if we want to prevent another Steubenville, the role of other girls must also be considered.

On the night in question, girls watched the victim (Jane Doe) become so drunk she could hardly walk. Why didn’t any of them help her? Why, after Jane Doe endured the agonizing experience of a trial in which she viewed widely circulated photos of herself naked and unconscious, did one of the arrested girls tweet: “you ripped my family apart, you made my cousin cry, so when I see you xxxxx, it’s gone be a homicide.” Why were two lifelong friends sitting on the other side of the courtroom?

The accusation of rape disrupts the intricate social ecosystem of a high school, one in which girls often believe that they must preserve both their own reputations and relationships with boys above all else. This is a process that begins for girls long before their freshman year and can have violent consequences.

From the earliest age, girls are flooded with conflicting messages about their sexuality. They are socialized to be “good girls” above all: kind, polite and selfless. Yet they are also told – via media images, the clothing that’s marketed to them and the messages conveyed by some adults – that they will be valued, given attention and loved for being sexy. The result is a near-constant anxiety about not being feminine or sexy enough.

Opinion: Steubenville case shows how the rules have changed

Get our free weekly newsletter

Meanwhile, girls consume romance narratives that tell them the most important relationships they can have are with boys who love them. They also observe a huge amount of psychological aggression among girls on television and in movies, often portrayed as comedy. Last year, researchers found that girls of elementary school age were more likely than boys to commit acts of social aggression at school after viewing them on television.

No surprise, then, that when the first crushes are confided in elementary school, it’s not uncommon for girls to turn on each other if they believe a friend is competing for the attentions of a boy they like. It often does not occur to them to reprimand the boy. This pattern is fairly innocuous in childhood, but by adolescence, it could have far more serious implications: Instead of grabbing the hand of a girl too drunk to consent and taking her to a safe place, some girls may instead angrily watch the drunken girl leave with a boy, figuring she deserves what she gets.

From late elementary school onward, the label “slut” hovers dangerously over girls’ every move. Most girls who are called sluts are not even sexually active. The word is used to distinguish “good” girls from “bad,” and the definition is constantly shifting. Few girls are let in on the criteria for who gets called a slut in the first place. The insecurity creates an incentive to call out someone else lest you be next.

In 2011, a study by the American Association of University Women found that girls in grades 7-12 were far more likely than boys to experience sexual harassment, including rumors, both in person and online. And Leora Tanenbaum interviewed 50 girls and women for her book, “Slut! Growing Up Female With a Bad Reputation;” all of them told her girls, far more than boys, were at the forefront of the slut rumor mill.

I am not saying that Jane Doe was raped because of girls’ silence. Girls may choose not to speak up for many reasons, but it’s hard to ignore the power of a culture that pushes them to choose boys over each other and punish other girls to protect their own reputations.

We must talk to girls about their responsibility in situations like this. If we want to prevent another Steubenville, we need to teach children from an early age about gender-based violence. The word “slut” is not just an epithet; it is a word that has given adolescents permission to abandon and hurt each other when a girl needs support most.

Girls must understand not only their moral obligation but their power to be allies to each other at parties and other potentially unsafe spaces for girls. If boys knew that girls banded together to support each other, they would be less inclined to share on social media, much less commit, these horrific acts of sexual violence.

Follow @CNNOpinion on Twitter.

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Rachel Simmons.