Story highlights

Third mate: Crew remained calm after Sandy tossed them into the Atlantic

Coast Guard hearings look for possible negligence

Before leaving port, captain gave crew option to go home

Shipyard representative says Bounty had rotted frame

Floating in a life raft with Hurricane Sandy raging around them, the crew of the HMS Bounty remained surprisingly calm and even told jokes after their ship rolled them into the Atlantic, survivors said.

Testifying Friday before a Coast Guard hearing, former Bounty third mate Daniel Cleveland and boatswain Laura Groves revealed breathtaking details about the shipwreck last fall that left a deckhand dead and the captain missing.

The vessel and its crew of 16 were heading from New London, Connecticut, to St. Petersburg, Florida, when it ran into Sandy’s vicious winds and waves 90 miles off North Carolina. The ship began taking on water and eventually it lost power to its pumps and engines. In the 4 a.m. darkness of October 25, Capt. Robin Walbridge gave the order they all knew was coming: abandon ship.

Dressed in red survival suits, they stood on deck preparing to take to their lifeboats. Suddenly 50-mph winds and up to 30-foot waves flipped the ship horizontally, tossing the crew overboard.

It was chaos.

“Everybody panicked at that point,” said Groves, fighting back tears as she described the struggle to keep their heads above water.

Cleveland said he recalled being “thrown around, caught on stuff and underneath stuff and being hit by things.” While they were treading water under the Bounty’s huge sails, the wind began slamming the sail rigging down “on all of us repeatedly,” said Groves. “We were doing our best to swim away from the boat and the rig.”

Cleveland, Groves and a few other crew members found a large piece of wood grating that kept them afloat. “We were all looking for each other,” Cleveland said, “but all you could see was a bunch of red suits and there was a lot of yelling.”

In a stroke of luck, the crew clinging to the wood grating found a floating capsule containing an inflatable life raft. With some difficulty they inflated the raft and got inside. They had seen a Coast Guard aircraft circling overhead, giving them confidence a rescue helicopter would arrive soon.

“We were there for a while telling jokes and stuff,” said Cleveland. “No one was in a bad mood – crying or anything.” He said they talked about the terrifying experience they’d just been through and “what we were going to do when we got home.”

“At some point we sang a few sea shanties,” recalled Groves. “We were in relatively good spirits.”

Dawn broke, followed by the the sound of a Coast Guard chopper, which dropped a rescue swimmer down to the life raft.

“He said, ‘Hi, I’m Dan,’” Groves remembered. “‘I heard you guys need a ride. Let’s get out of here.’”

While the swimmer was helping survivors get out of the life raft, it flipped upside down. “We all thought we were going to drown again,” remembered Groves. Instead, they swam out of the raft and held on to the outside until the chopper hoisted them to safety.

Related: Watch Bounty survivors being rescued

Meanwhile the Bounty – a replica of an 18th-century sailing ship that was longer than half a football field and weighed about a million pounds – was descending to the bottom of the Atlantic.

During his testimony, Cleveland was asked about the last time he saw deckhand Claudene Christian, 42. More than three months after the shipwreck, the exact circumstances surrounding her death remain unclear. Before the ship rolled, Cleveland said he remembered holding Christian’s hand as he helped her and other crew members prepare to launch the life rafts. Searchers found Christian’s body later that evening.

Related: Claudene Christian’s mutineer connection

The final glimpse Cleveland got of Walbridge, 63, was just before the ship went on its side.

Walbridge’s body has not been found. His widow said she believes the captain died trying to help Christian escape.

Related: Bounty’s captain was ‘my soul mate’

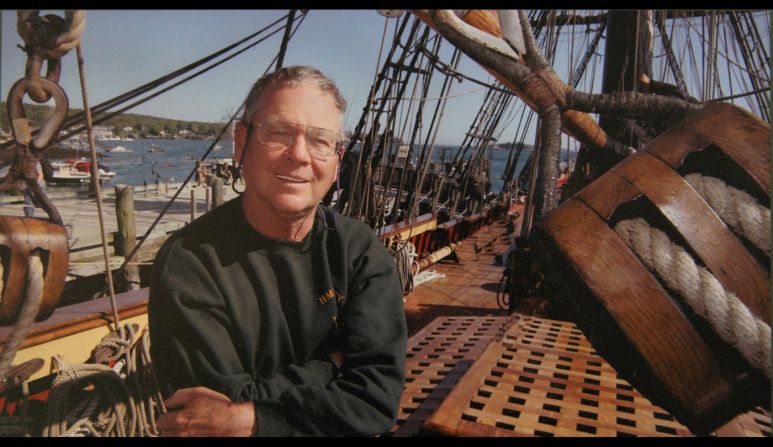

Bounty was much more than a creaky 50-year-old wooden tourist attraction. It was a bona fide Hollywood star, featured in the 1962 film version of “Mutiny on the Bounty,” which starred Marlon Brando, and more recently in the “Pirates of the Caribbean” franchise that starred Johnny Depp. But it also was a ship where inexperienced sailors could learn seafaring skills that go back hundreds of years.

The hearings, which include the National Transportation Safety Board, could lead to federal recommendations aimed at improving safety for other ships like the Bounty.

Investigators in this military shipyard region near the mouth of Chesapeake Bay have been asking two basic questions: Was the Bounty fit to sail in rough weather? And did the ship needlessly sail into harm’s way?

About two months before the disaster, Walbridge, a master sailor with a lifetime of experience at sea, played down the seriousness of sailing through bad weather. “Have we run into stormy seas? We chase hurricanes,” Walbridge said in a video interview posted on YouTube. “You don’t want to get in front of it,” he said. “You want to stay behind it, but you also get a good ride out of a hurricane.”

Asked about that comment by Walbridge, Cleveland testified that the captain didn’t mean literally chasing hurricanes. “It means we are trying to follow them into a navigable, safer” area of the storm, he said. The idea was “getting behind it, in a safe place” to make use of its favorable winds. “You don’t want to be in its path.”

Before the ship set sail from New London, the crew was very aware of the approaching hurricane, Cleveland said. Walbridge gathered them for a meeting in which he “mentioned his experience with hurricanes and he said if anybody wanted to leave there would be no hard feelings, no begrudging.”

“I believed him,” said Cleveland, who was then asked if the crew were offered paid expenses home. “In my experience, if you choose to leave, you would have to find your own way home.”

“Nobody decided to leave,” Cleveland said.

Walbridge said he wanted to “make tracks” to the south and east as fast as possible, Cleveland said, so the vessel could position itself to get the best winds from Sandy.

The captain believed, Cleveland said, that his ship would be safer riding Sandy out at sea, instead of waiting for the storm to hit them in New London. Cleveland said he agreed with that point of view, but there were also good arguments to remain in port.

Bounty first mate John Svendsen testified Tuesday that Walbridge wasn’t chasing Sandy, but the captain had said “the ship was safer at sea.”

Svendsen testified that as the storm worsened on October 29, he advised Walbridge to abandon ship more than once over a short period. “He said, ‘I think we have more time.’” When Svendsen made a third request to the captain to abandon ship, he said Walbridge finally gave the order.

While the 13 other crew members, including Groves and Cleveland, made it safely to two life rafts, Svendsen spent three hours floating alone in his survival suit before Coast Guard rescuers saw his emergency beacon.

The Coast Guard said its goal for the investigation is to determine as much as possible about the cause of the tragedy and whether it was linked to equipment or material failure. Investigators are looking for evidence of “misconduct, inattention to duty, negligence or willful violation of the law.”

Did Walbridge make a fatal error? People who weren’t there have no right to pass judgment, the captain’s widow, Claudia McCann, said last week from her home in St. Petersburg.

Although it’s not a criminal hearing, Bounty owner Robert Hansen declined to testify, citing his Fifth Amendment constitutional protections against self-incrimination. Evidence could be forwarded to federal prosecutors.

In Thursday’s testimony, Todd Kosakowski of Maine’s Boothbay Harbor Shipyard said he raised doubts about Bounty’s seaworthiness weeks before it sailed into the storm. He said he told Walbridge he was worried about rotting wood in the Bounty’s frame. Walbridge, Kosakowski said, decided against fixing the rot.

“I believe that that could have had an impact on the strength of the vessel,” Kosakowski said.

Joe Jakomovicz, a retired manager who worked at the shipyard for four decades, told investigators he disagreed with Kosakowski’s analysis. The decay of the Bounty’s timbers, he said, wasn’t as bad as Kosakowski’s assessment. “He’s basing his judgment on probably five or six years of experience,” Jakomovicz testified.

Claudene Christian’s father, Rex, and her mother – who shares her daughter’s first name but goes by Dina – were also at the hearing. For now, they’ve declined to speak with reporters.

Their daughter was relatively new to sailing, and told friends in May how excited she was to join the Bounty. A former beauty queen, Christian also said she was a descendant of Fletcher Christian, the infamous mutineer on the real HMS Bounty 220 years ago.

On Friday, her mother sat silently at the side of the hearing room, dabbing her eyes with a handkerchief and sometimes taking notes.

The memory of Claudene Christian took a seat at the proceding almost as real as any of the participants.

Several questions focused on the energetic deckhand who had virtually no experience aboard a tall ship, let alone riding out hurricanes. When Cleveland helped her move toward the back of the ship, shortly before it went horizontal, he “told her to stay low. I told her to go aft and to grab the next person I would hand her to.”

She never made it home.

During a brief recess, Christian’s parents paused at a window near the hearing room in this shipyard town, their arms around each other, looking across the Elizabeth River flowing toward the sea.

CNN’s John Couwels contributed to this report.