Editor’s Note: Paul Varian is a senior executive producer at CNN who worked as United Press International’s deputy managing editor and foreign editor in New York and Washington. He joined CNN in 1984.

Story highlights

Many famous, and infamous, Americans are buried at Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery

For 75 years, the author's grandfather was buried there without a marker

Recently, the family located his grave site and commissioned a headstone

It was the last stop for some of New York’s finest and most reviled: famed composer Leonard Bernstein, “Boss” Tweed, and organized crime’s “Lord High Executioner,” Albert Anastasia – shot dead in a barber’s chair in 1957.

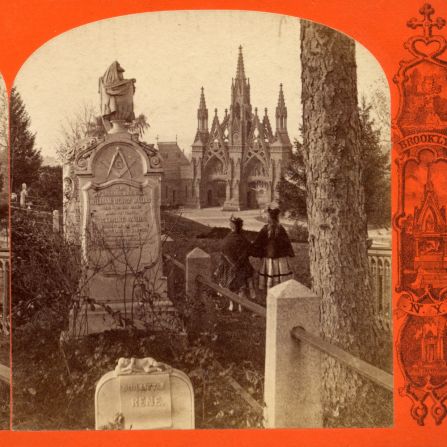

Civil War generals, inventors, baseball legends, so many who helped define American history – in good ways and bad – are buried at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery. Today, their headstones are places to visit on daily tours of the 175-year-old cemetery, a stately presence in an otherwise scruffy neighborhood.

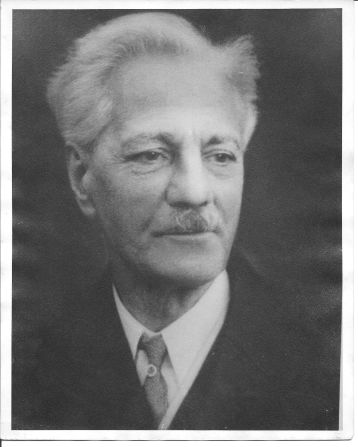

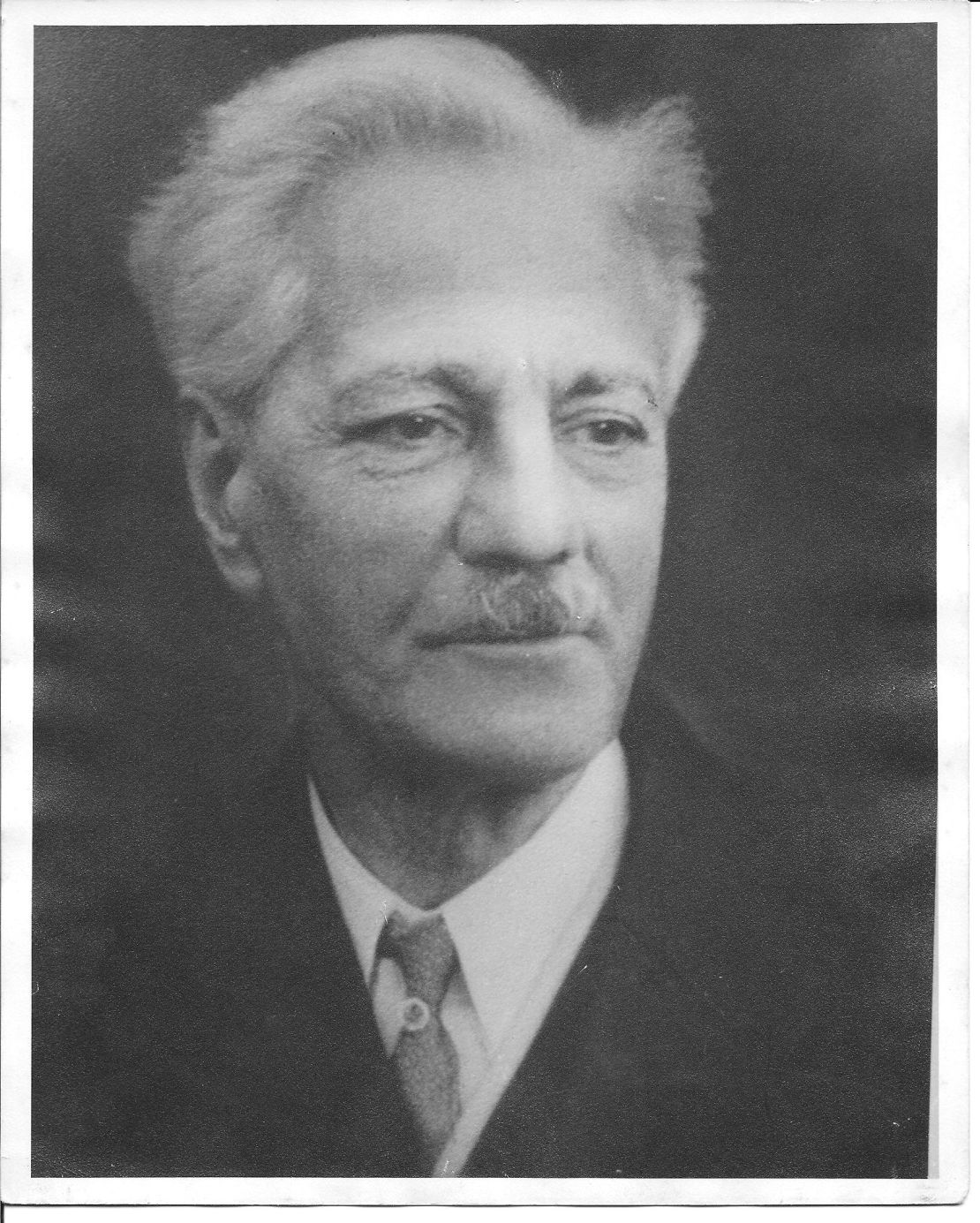

There was no such marker there for my grandfather, Henry H. Varian, a newspaperman of some renown who toiled for the likes of Hearst and Pulitzer.

A survivor of shipwrecks who rounded dangerous Cape Horn five times during his years as a sailor before the Panama Canal opened, he claimed to have read his own premature obituary three times – once after nearly drowning and twice following serious accidents.

Nobody can explain now precisely why Henry Hudson Varian – the full name he used as a byline on essays and some of the poems commonly published in newspapers in those days – was buried without a headstone.

This fall, 75 years after his death, several generations of his family from up and down the East Coast came together to mark the grave of a man most of us never knew who started a journalistic tradition spanning more than a century, that endures to this day.

Pearl Harbor survivor helps identify unknown dead

Search for grave site

First, we had to find exactly where my grandfather was buried – a task speeded by technology few could have conceived in his day: a mobile phone my son Michael used to pinpoint the burial site amid Green-Wood’s 478 acres of rolling hills, paths and glacial ponds with nearly 600,000 “permanent residents.”

Michael, a New Yorker, was part of the family entourage led by my godmother, Frances Campbell – Henry Varian’s only surviving child, now a widow in her 80s – who had journeyed from Virginia, Maryland, Georgia and New Jersey.

“I was so excited about that, you can’t imagine, to see all the Varians together,” said Aunt Frances. “It was just wonderful. I couldn’t believe it was happening.”

After finding the grave, we headed across the street to the Brooklyn Monument store, a small, cluttered house that showcased the rich history of the cemetery, whose sprawling grounds had been a Revolutionary War battlefield before becoming a burial place.

A large framed picture on a wall in the back room brought back one of my happiest childhood memories – it was the team photo of the 1955 Dodgers, who brought the first and only World Series baseball championship to Brooklyn.

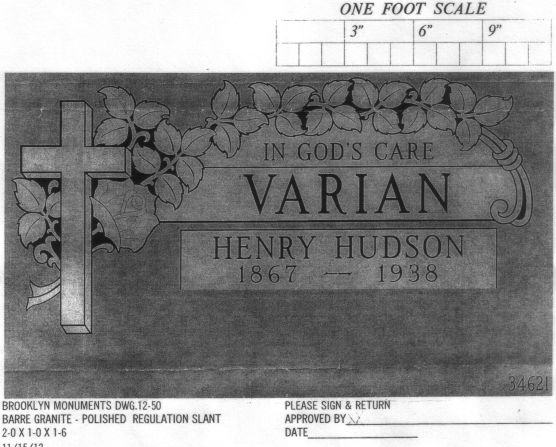

Outside was a small “garden” where Monica Hakola, wife of the store’s owner, helped us pick out an appropriate headstone.

My godmother liked the one with the rose-leaf pattern because her father once wrote her a poem – also published in his newspaper – titled, “The Rose of New Rochelle.” The rest of us agreed and she quickly handed over a cash down payment.

Aunt Frances is the only surviving member of the family with memories of my grandfather, who died nearly a decade before I was born.

His photograph sat on our living room piano throughout my childhood, but I knew almost nothing about him – until now.

Overseas burial ground honor fallen Americans

High seas adventurer turned newspaperman

Born in 1867 in Liverpool, England, Henry Varian was one of 13 children of an Irish lawyer and Brazilian-born mother of Spanish heritage. He went to college in Wales and studied art in Dublin, then decided to go to sea as a midshipmen.

He came ashore in the United States at age 19, where he worked at several newspapers on the West Coast and in Chicago as a reporter before heading to New York. There, he rose to high-level editor positions at several newspapers.

All but two of the publications where he worked over a 38-year career – San Francisco’s Chronicle and the currently online-only Seattle Post-Intelligencer – reside in newspaper graveyards today.

His first job was with the San Francisco Call, where he covered violence during a railroad workers strike that led to the establishment of Labor Day. In another major assignment, he reported on the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair for the Chicago Mail.

Moving east, he became executive editor of The New York Globe and then moved to Pulitzer’s World, where he directed coverage of the Spanish-American and Boer wars as foreign editor and waged campaigns against the vice rackets, fortune-tellers and organized prostitution as city editor.

“He held all the important executive positions on the World,” said his December 4, 1938, obituary in the Brooklyn Eagle.

Always faithful: Marine veterans tend to hero’s grave, cemetery

His career was cut short as a result of a near-death experience. On his way home in Brooklyn one night, he was run over by a speeding streetcar while crossing Flatbush Avenue and “dragged 20 feet,” according to a March 22, 1915, New York Times account headlined:

“Henry Varian, Hit By A Car, May Die”

He didn’t for another 23 years, but he suffered severe injuries that eventually led to blindness, including a compound skull fracture and, the Times said, “almost his entire right side has been crushed in.”

A year later, he became a widower. He remarried and had two more children – my father, another career newsman, now deceased, and daughter Frances.

He went blind before Frances’ birth, yet the two were very close, she recently recalled. She never really thought of him as being blind.

“At Christmastime every year, he’d knock on my door and say, ‘Let’s go down and see what is there,’” she said. “He walked down the stairs with no problem – he had his own way of doing it.”

Henry Varian retired because of his blindness in 1927 and died little more than a decade later at age 71. It was the height of the Great Depression. The family moved from its comfortable suburban home in New Rochelle, New York, and his only son – my father – walked away from a college football scholarship and got a job to help support the family.

He eventually followed in his father’s footsteps, first as a newspaper reporter in upstate Binghamton, New York, and, after fighting in World War II, as a photo editor for Acme Newspictures, which was taken over by United Press in the fledgling days of still picture journalism.

That led to two more generations of journalists – myself, and then my oldest son, Bill, a newspaper reporter for more than two decades, now with the Tampa Bay Times.

In a family of storytellers, the story of my grandfather’s unmarked grave remains an enigma. The one person who might be able to explain it, Henry Varian’s widow – my grandmother Martha – died in 1991 at the age of 102.

“I knew there was something that was missing,” her daughter, my Aunt Frances, told me recently. After an earlier visit to the cemetery nearly 10 years ago, she began saving to buy a headstone.

A father seeks peace in a place of war

Honoring my grandfather

My relatives and I visited Green-Wood a few weeks before Superstorm Sandy toppled many of its towering trees, badly damaging scores of monuments and headstones.

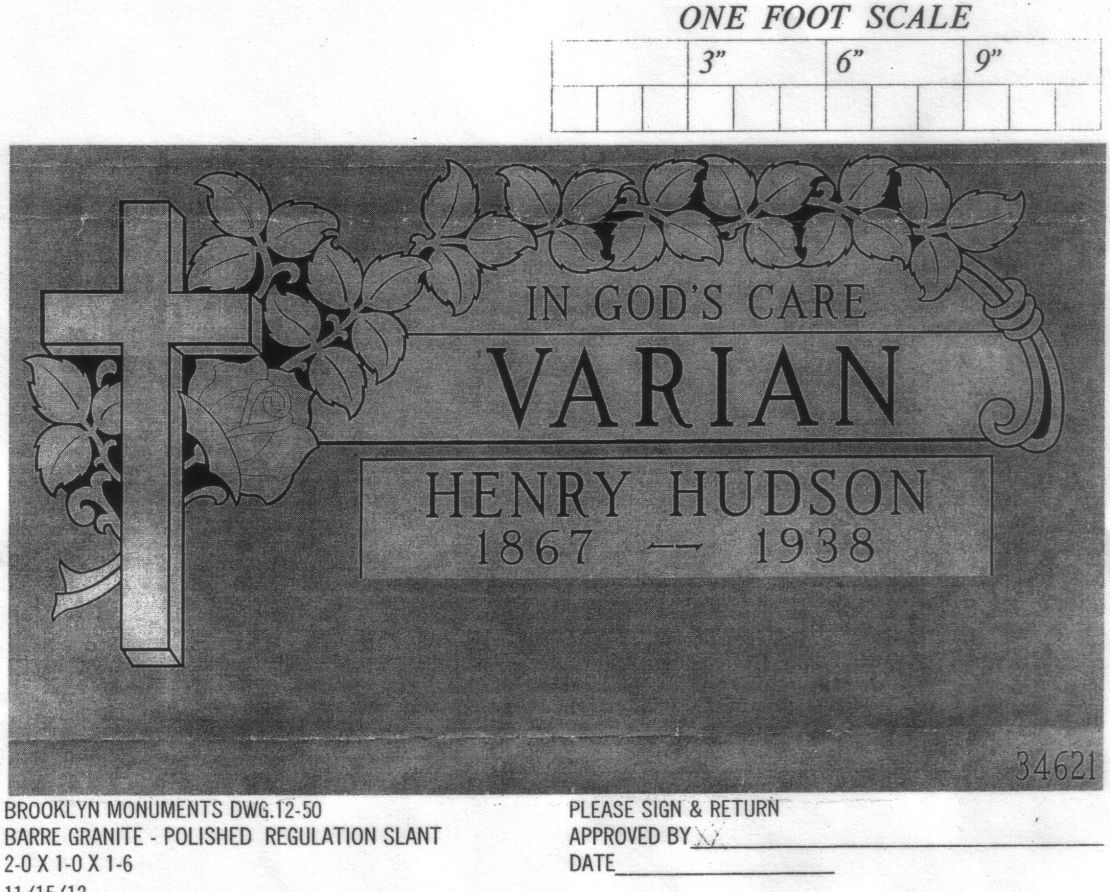

But not my grandfather’s. A bit more paperwork needs to be completed before his headstone is placed in the earth. It reads:

In God’s Care

VARIAN

Henry Hudson

1867 – 1938

Bringing to mind one of his shorter but most poignant poems that appeared in the New York World. Its title: “Life.”

Vain is our life.

A little love

A little strife

And then – Good Den!

Our life’s a glean

A flash of hope

We dream a dream

Then sigh – Good-by

Have you investigated your family history? Share your story.