Editor’s Note: Michael Y. Simonis a psychotherapist, school counselor and founder of Practical Help for Parents, a support organization for parents, educators and mental health professionals. Simon is also the author of The Approximate Parent: Discovering the Strategies That Work with Your Teenager (Fine Optics Press, 2012).

Story highlights

Michael Simon: We don't know how to make sense of tragedy, but our kids want our guidance

He says media accounts come faster than brain can process complex emotions, empathy

He says study shows deluge of news interferes with ability to help others with their emotions

Simon: To respond to suffering of kids, loved ones: slow down, give persistent, calm attention

I don’t have the answers.

Under the weight of mystery, loss and grief, most of us long for healing and look for answers. After hearing of the mass killing in Newtown, Connecticut, I asked a friend, the principal of an elementary school, how the children and parents there were doing.

“There was a different feeling and a much longer line than usual to pick up the kids,” he said “Hugs held longer, smiles broader, more patience all around; these parents were mindful of the privilege of picking up their children today.”

Not including the tragic killings at Sandy Hook, the Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence lists over 170 school shootings in the United States since 1997, prompting many to describe the tragic shooting as part of an epidemic of gun violence in America.

How do we make sense of these incidents and their antecedents and envision a better future? I don’t know, and neither do many of the so-called experts, but that hasn’t stopped them and the mass media from weighing in very quickly.

Opinion: Parents’ promise: I will keep you safe

Get our free weekly newsletter

We’ve seen this all before: Media outlets rush to feed the voracious hunger of the 24-hour news cycle, reporting on instant theories and repeating rumors and mistakes, sometimes supplied by well-meaning law enforcement and school officials eager to provide information to anxious parents. Pundits rush to defend or denounce gun control or render judgments about the mental health system.

Tweets and texts fly, fingers wag in consternation at all those who got the facts wrong. Theories, reasons and blame pile up. Unbridled arguments break out – check the comments under this piece, and most other pieces online.

Meanwhile, our young children are watching, listening and looking to us for answers.

They need us calmly close by, a loving, attentive presence quietly assuring them that their world will not change. It scares us to our depths because we know we cannot really promise that.

Opinion: Mourn … and take action on guns

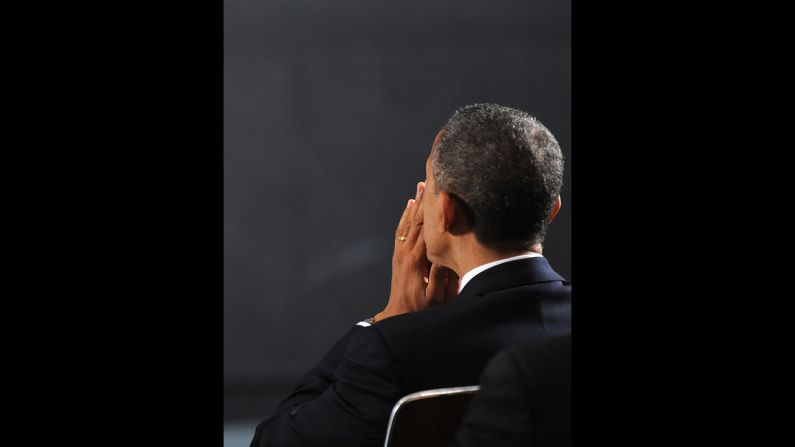

To calm a shocked nation, President Barack Obama appeared on television as events were still unfolding in Newtown. After expressing heartbreak for the slain children and their parents, he spoke of the parents whose children had survived: “Their children’s innocence has been torn away from them too early and there are no words that will ease their pain.”

If there are no words, then what is there? The president’s tearful reaction was notable for several long pauses as he struggled to prevent his feelings from overwhelming the need to communicate to a nation in grief.

Obama’s pauses were bookends to his observation that “our hearts are broken today.” They point to necessity of time for any deep, effective, moral and compassionate response to pain and loss. A 2009 prize-winning study done by Mary Helen Immordino-Yang, Antonio Damasio and their colleagues at the Brain and Creativity Institute at the University of Southern California could be seen as a kind of scientific exploration of what it means to have “our hearts broken.”

Support crucial for kids after trauma

Immordino-Yang put it simply:

“The poets had it right all along. This isn’t merely metaphor. Our study shows that we use the feeling of our own body as a platform for knowing how to respond to other people’s social and psychological situations.”

Martin: Now is the time to talk guns, mental illness

But the speed of our digitally mass-mediated lives is not conducive – according to Immordino-Yang and Damasio’s work – to experiencing the “nobler instincts” of empathy and compassion in response to violence and human suffering.

The USC study demonstrated that when people heard stories depicting physical pain, the pain centers of their own brains activated very quickly. But empathizing with stories of psychological pain took much longer. Seeing or hearing stories of physical injury and death – the stock in trade of much media – does deeply and quickly move us. But the higher emotions and the capacity for an ethical response, compassion and empathy, “are inherently slow.”

Immordino-Yang surmises, “For some kinds of thought, especially moral decision-making about other people’s social and psychological situations, we need to allow for adequate time and reflection.” She warns that if the flow of information and news is too quick, it can interfere with the experiencing of emotions about other people’s psychological states, a problem she argues has “implications for your morality.”

By slowing down and recognizing the need for time to ethically respond to suffering, we see the faint echoes of an answer to the question of whether our children can live in this imperfect world and still feel free and hopeful (and whether we can do the same).

Manuel Castells, Wallis Annenberg Chair of Communication Technology and Society at USC, thoughtfully summarized Damasio’s study: “Lasting compassion in relationship to psychological suffering requires a level of persistent, emotional attention.”

Persistent, quiet, calm attention: This is what our children need from us in the wake of this horror, and what we owe one another as we stumble along trying to figure out what to do about it all. It suggests that deep listening, rather than quickly speaking (or cajoling, warning, or advising our children and each other) may provide the time we need to experience our “nobler instincts” in the face of all-too-human grief and loss. I don’t have the answers. But I suspect that answers will come — slowly.

Follow @CNNOpinion on Twitter

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Michael Simon.