Editor’s Note: Julian Zelizer is a professor of history and public affairs at Princeton University. He is the author of “Jimmy Carter” and of the new book “Governing America.”

Story highlights

As deadline approaches, officials trying to find a solution to tax/budget issues

Julian Zelizer: President Obama should look at how former presidents handled such issues

Clinton broke promise not to raise middle class taxes; LBJ cut spending deeply

Presidents who anger their party's base can use that to help reach a deal, he says

Most officials in Washington are dreading the consequences of falling off the fiscal cliff.

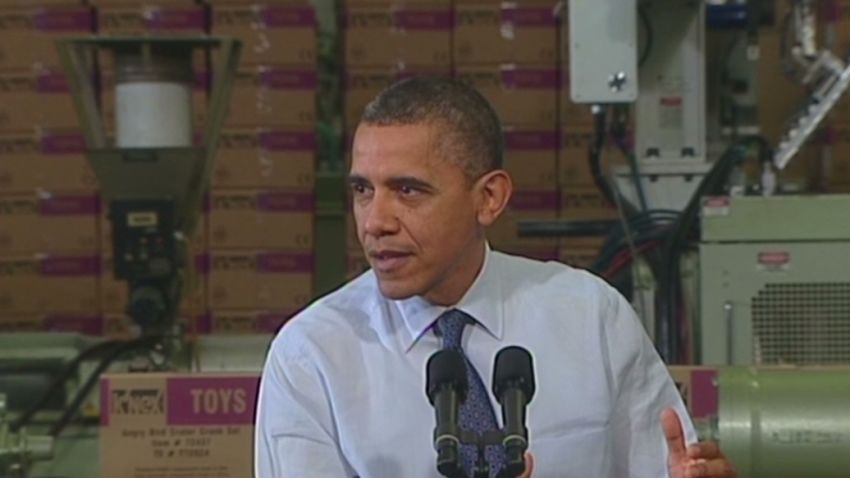

President Barack Obama and his advisers have met in the White House trying to figure out a deal that will protect them politically while avoiding the draconian deficit reduction option that will occur should the parties fail to reach agreement. And on Friday he traveled to a Pennsylvania toy factory to seek public support to pressure Congressional leaders to pass legislation extending tax cuts for middle-income Americans.

Obama is not the first president to confront the challenges of deficit reduction, one of the least pleasant tasks in politics because it forces elected officials to take things away from voters rather than do what they prefer: hand out benefits. In the next few days, the president would do well to look at how previous chief executives have handled this task.

In 1967 and 1968, in a period of united government and regionally divided parties, President Lyndon Johnson grudgingly undertook a brutal campaign to push through Congress a 10 percent tax surcharge and spending cuts to curb the growing size of the federal deficit that had resulted from spending on Vietnam.

Under pressure from Southern Democrats who controlled the key committees and their Republican allies, Johnson agreed to much steeper spending cuts than his advisers wanted him to so that he could get the package through the House and Senate.

Get our free weekly newsletter

Many liberals were furious with the president, believing that he had sold them out and placed their programs in jeopardy. But Johnson had become convinced that the deficit reduction passage was essential to stabilize the dollar in international markets and ensure that the federal government had enough revenue to keep most of his domestic programs intact.

In 1990, President George H.W. Bush undertook one of the most embarrassing about-faces in modern politics. Though he had promised in his 1988 acceptance speech, “Read my lips, no new taxes!” two years later Bush agreed with Democrats on a deal that implemented major restraints on spending while increasing taxes.

The decision caused a firestorm. “Read My Lips: I Lied” said the New York Post. Republicans like Congressman Newt Gingrich were furious with his decision. To overcome this opposition, Bush took to the airwaves, making a speech in which he directly appealed to citizens to build support for this. Bush watched as his approval ratings plummeted. Gingrich refused to have his picture taken with Bush at the Rose Garden and publicly criticized the president.

Three years later, President Bill Clinton took a stab at the deficit that continued to grow despite the 1990 deal. After the election of 1992 had made deficit reduction a major issue he used all his partisan muscle to push through Congress an increase in taxes for Americans earning $125,000 or more.

Clinton abandoned his campaign promise that he would not raise taxes on the middle class. He allied with fiscal conservatives such as Alan Greenspan, chairman of the Federal Reserve who were insisting on deficit reduction. The bill was hugely unpopular. Every Republican voted against the bill, along with some blue dog Democrats. Many liberal Democrats felt that he had betrayed them. The final package increased tax rates and enacted spending cuts.

Marjorie Margolis-Mezvinsky, a freshman Democrat who the administration pressured into casting the decisive vote in the House despite her knowing it would be politically devastating and despite her earlier opposition, lost her seat, as expected in 1994. “Goodbye Marjorie,” Republicans had yelled when she voted. Clinton ended up benefiting politically from this controversial decision, as the economy boomed and deficit disappeared by the end of the decade, both providing his most lasting legacy.

Angering the base is clearly part of what lies ahead for President Obama. Johnson, Bush, and Clinton all cut against what core members of the party wanted to reach a deal.

At the most basic level, Obama will need to win enough House Republican votes for a deal and this will entail more cuts in domestic spending than liberals want to swallow. Equally important, the president will have to win over moderate Democratic senators who are nervous about reelection.

In addition to helping achieve compromises on specific numbers, angering the base also has symbolic value to the White House. The criticism from supporters demonstrates that a president is bending over backward, pushing as far as he can, thereby offering an incentive for the other party to shift closer to the center.

The president will also need to use the bully pulpit to sell the idea of sacrifice combined with the promise of growth. Obama must not simply work in closed rooms with House Speaker John Boehner. He must continue to take to the airwaves to build support for the bill. With regards to sacrifice, he must explain to voters why hard choices are necessary. He must tap into the legacy of Clinton by outlining the long-term economic rewards that could come from a good deal.

Obama must also consider breaking some promises that he has made along the way. Johnson started his presidency by reducing taxes and assuring Congress he would not raise taxes to pay for his program. Bush did the same, as did Clinton. But when dealing with major challenges this is necessary.

Effective politics is often about the need to be flexible. More than almost any other issue, deficit reduction requires this skill given that all the tradeoffs are unpopular. This might include being flexible on his assurances to avoid raising taxes on the middle class.

Finally, the president will need to employ all the partisan muscle that he has. In 1993, Clinton famously leaned on Democrats who were dragged along kicking and screaming. Politics ain’t bean bag, as the saying goes, and Obama must act like a tough partisan to win.

Achieving a deal won’t be easy and it won’t be fun. But a deal is possible if the president throws all of his weight behind the effort.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Julian Zelizer.