Editor’s Note: Frida Ghitis is a world affairs columnist for The Miami Herald and World Politics Review. A former CNN producer and correspondent, she is the author of “The End of Revolution: A Changing World in the Age of Live Television.” Follow her on Twitter: @FridaGColumns

Story highlights

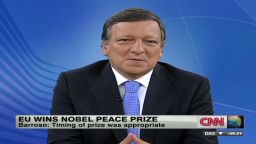

The Nobel Committee awarded the Peace Prize to the European Union

Frida Ghitis: What a sadly missed opportunity

She says the committee passed on chance to put global spotlight on person or cause

Ghitis: Peace Prize can make a difference; this time it was supremely uninspired

So many tyrants to resist, so many heroes to support, but the Nobel Committee decided to ignore all of that and grant the Nobel Peace Prize this year to a large bureaucratic political alliance, the European Union.

The committee passed up a chance to give a tangible boost to and put the valuable global spotlight on an individual, a cause or an organization that could really benefit from the award. What a sadly missed opportunity.

Peace Prize is a slap on the back for a struggling European Union

Malala Yousafzai, the 14-year-old Pakistani girl shot by the Taliban for advocating girls’ right to an education, is precisely the kind of person who should have inspired those making the selection. There’s only one Malala, but there are countless people around the world doing heroic work every day, many risking their lives to end tyranny, hunger and illiteracy.

I have nothing against the EU. It has accomplished important things, and the Norwegians who award the Peace Prize surely wanted to give it recognition during a time of economic turmoil and political tension in Europe.

Still, the Norwegian Nobel Committee wasted the moment.

We are living through a time when competing forces are fighting for radically different visions of the future. Activists for democracy, for women’s rights, for religious tolerance have faced off against state security forces, religious extremists and brutal misogynists. Zealous prosecutors, loyal to authoritarian regimes, have imprisoned artists, executed homosexuals and tortured democracy activists.

Those permitted to nominate candidates gave the panel ideas, a dazzling collection of extraordinary organizations and individuals.

The list will remain secret for half a century, but that didn’t keep people from speculating about who might win.

The favorites included Sima Samar, a doctor and human rights activist who served as Afghanistan’s women’s affairs minister until she was forced out with death threats for challenging laws that oppress women. There’s Maggie Gobran, a Coptic nun in Egypt whose Stephen’s Children charity helps Christian children living in Cairo’s slums.

In Nigeria, where clashes between Christians and Muslims have left hundreds dead and threaten to tear up the country, Archbishop John Onaiyekan and Sultan Sa’ad Abubakar are fighting for reconciliation. In Cuba, blogger Yoani Sanchez struggles for democratic reform in and out of jail, as do other dissidents languish in prison.

In Russia, where journalists who criticize the government turn up dead much too frequently, the number of courageous writers and artists standing up for reform includes many courageous figures.

The list goes on and on. And, in case anyone doubts just what a difference the Nobel Peace Prize can make, consider some of the inspired choices the Norwegian panel has made.

The military junta ruling Burma, which renamed the country Myanmar, had locked up pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi, whose party, the National League for Democracy, won the 1990 election. When she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991, her cause – the plight of the Burmese people – became the world’s struggle. She was not allowed to travel to Oslo for the awards ceremony. But the Burmese people discovered that they were not alone. After many years, including more than a decade of house arrest, she was set free in 2010. She traveled to Oslo to receive the prize in person, and now it looks as though Burma stands at the threshold of freedom.

The Peace Prize of 1975 drew attention to the work of Soviet dissident Andrei Sakharov, the physicist who became, in the committee’s words, “a spokesman for the conscience of mankind.” He spent years in exile in Siberia, but his work helped forge the nuclear test ban and international cooperation. The award became a megaphone for his ideals.

In the past, the Nobel committee has proved daring and controversial. This time, it was supremely uninspired.

Nonviolent figures such as the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., the Dalai Lama and Poland’s Lech Walesa became household names because they received the prize. Their protest techniques became subjects of academic study and practical guidance around the globe. Their selection inspired last year’s winner, Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo, author of “No Enemies, No Hatred,” another of several Nobel winners who could not attend the awards ceremony because their governments put them in prison or banned them from traveling.

The Nobel spotlight can bring donations and needed publicity to a cause. The push for a landmines ban started making headlines after Jody Williams and her Campaign to Ban Landmines won in 1997.

True, the committee’s choice always upsets some people. But it’s more frequently because of boldness than blandness.

Naturally, the choice can be politically charged. After Barack Obama won in 2009, with just a few months in office, it left many scratching their heads. When told of the announcement, Walesa said, “Who, Obama? … He hasn’t had the time to do anything yet.”

Obama went on to stun his hosts when he received the award. His Nobel lecture turned out to be a brilliant exposition of when war becomes a requirement for peace. It was not exactly what they expected from a Nobel Peace Prize winner. The decision reflected the committee’s hopes more than Obama’s achievements. The panel wanted Obama to become the president of peace. He accepted the award, but it turned out he was not a pacifist.

The choice for this year also reflects aspirational views. The Norwegian Nobel Committee, selected by Norway’s parliament and made up mostly of politicians, is telling the world, specifically Europeans, that they should do whatever it takes to save the European Union. It is asking them to remember that Europe, the continent that in the 20th century perpetrated the worst wars the world has seen, has managed to stay mostly at peace for almost 70 years. The committee gives the credit to the EU. It was a retrospective award, a historical analysis.

What the committee should have done was use this chance to take sides and to speak in a way that makes a difference in favor of freedom, equality and tolerance.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Frida Ghitis.