Story highlights

NEW: Vidal was "the godfather of gay literature," author says

He died of complications from pneumonia, his nephew says

He wrote more than 20 novels and appeared in a number of films

He unsuccessfully ran for office twice

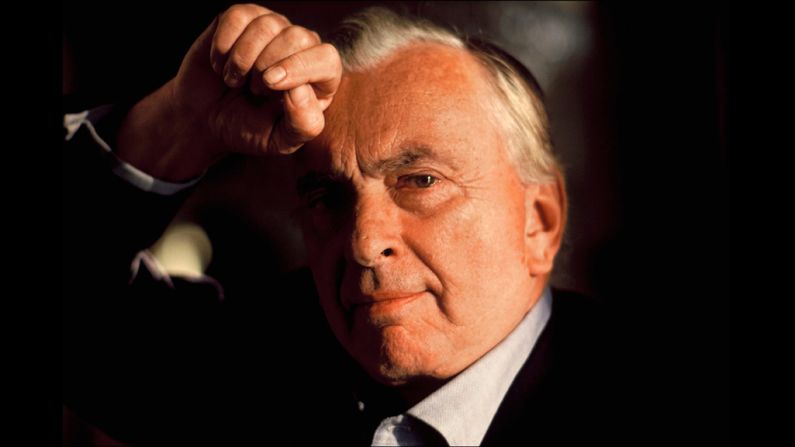

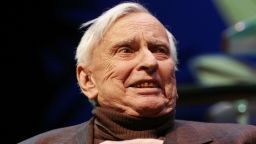

Gore Vidal, the eclectic author who faithfully chronicled the major shifts and upheavals in the United States in books, essays and plays, has died. He was 86.

Vidal died at his Los Angeles home Tuesday evening of complications from pneumonia, his nephew Burr Steers said. The author had also been suffering from heart ailments.

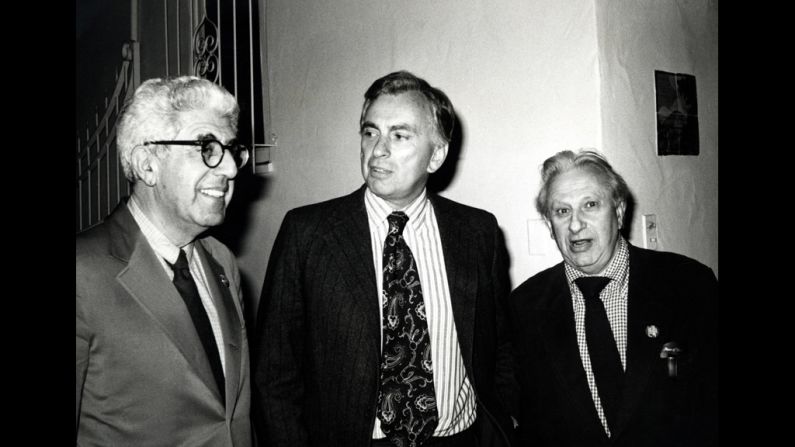

Widely hailed as one of America’s greatest men of letters, the aristocratic Vidal was a high-profile commentator on politics, including his bitter opposition to the war in Iraq and his belief that the United States had betrayed its humble roots to become an imperial power.

Tribute: My friend, il maestro Gore Vidal

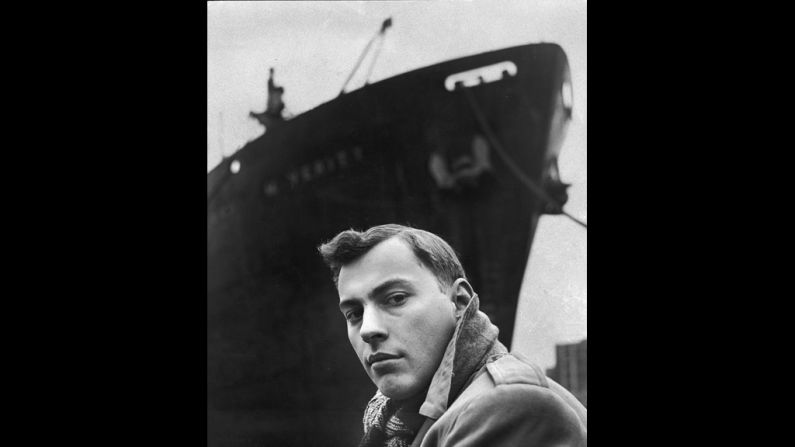

Born into politics as a member of a rich and powerful family, he joined the Navy at 17 before shocking the world by writing one of the first novels to include an openly gay character: his 1948 work, “The City and the Pillar.”

“He was the godfather of gay literature in spite of himself,” said Christopher Bram, author of “Eminent Outlaws,” a profile of the groundbreaking homosexual authors of Vidal’s era. “He really didn’t want the title for himself, but he wanted to be acknowledged as being important to gay people.”

In all, Vidal wrote some 25 novels, two successful Broadway plays, numerous screenplays, more than 200 essays and the memoir “Palimpsest.” His collection of essays “United States: Essays, 1952-1992” won the National Book Award in 1993, while a revival of his play “The Best Man” – about the backstabbing and deception surrounding a national political convention – was nominated for a Tony award this year.

A look back at his accomplishments

Vidal also appeared in a number of films, including the political satire, “Bob Roberts,” where he played a U.S. senator. He twice ran for office himself: as a candidate for Congress from upstate New York in 1960, calling for the recognition of Communist China, and later as a Senate candidate in California in 1982, which became the subject of a documentary.

Throughout his life, Vidal didn’t shy away from controversy – either actively courting it or inviting it through his acerbic one-liners.

He riled the right by saying the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks occurred because the Bush administration was “incompetent” and Bush himself was “inactive and inopportune.” Vanity Fair refused to publish an essay he wrote reflecting on the tragedy.

He ruffled others by befriending convicted Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh and saying he understood “why he did what he did.” The more they communicated, the more impressed he was by McVeigh, Vidal said.

His book “Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace: How We Got to Be So Hated” takes the position that both attacks were provoked by “our government’s reckless assaults upon other societies.” A firestorm of criticism followed.

“I’ve had hard targets in my lifetime, I’ve taken on general superstitions, but that’s what writers do. So I certainly, wouldn’t have changed my modus vivendi one bit,” he said of the furor.

Vidal “was always a gadfly,” Bram said. “But in the last 10 to 15 years, it turned into this very bitter, not always rational anger with American government across the board. Conservatives, liberals – he disliked them all, and could be intensely critical of them all.”

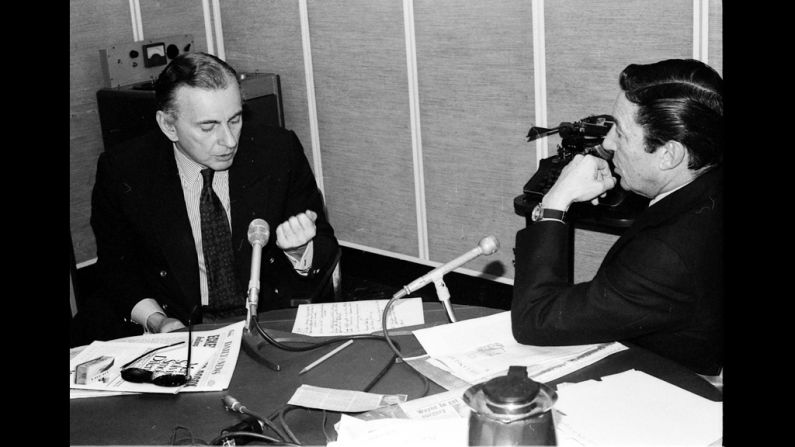

Vidal often appeared on the television talk show circuit, going head-to-head with those with opposing viewpoints – and gave as good as he got.

Opinion: Vidal’s strengths and weaknesses

He once compared author Norman Mailer to the infamous killer Charles Manson, which prompted Mailer to head-butt him before a show. Author Truman Capote once said he felt sad about Vidal, “very sad that he has to breathe every day.”

And in a live TV debate, conservative author and journalist William F. Buckley Jr. famously called him “queer.” To be fair, Vidal had called him a “crypto-Nazi” first.

“Well, I mean I won the debates, there was no question of that,” Vidal recounted in a CNN interview in 2007. “They took polls, it was ABC Television. … And because I’m a writer, people think that I’m this poor little fragile thing. I’m not poor and fragile. … And anybody who insults me is going to get it right back.”

He also voiced himself on the animated show “The Simpsons.”

Vidal would say he was a once-famous novelist who was relegated to going on television because people “seldom read anymore.”

“All these literary prizes should go to the readers: ‘Nobel Prize for the best reader in Milwaukee,’ ” he said. “And you know, we must honor them because they are so few.”

But the truth is, Vidal, all his life, relished his role as provocateur, as an anti-establishmentarian, as a self-proclaimed conspiracy “analyst.”

Relishing his role

He was born Eugene Luther Gore Vidal on October 3, 1925.

His grandfather, T.P. Gore, helped write the state constitution of Oklahoma. His father, Eugene, played professional football, competed in the decathlon in the Antwerp Olympics in 1920 and, as an aviator, was instrumental in expanding the U.S. aeronautics program.

And when his mother, Nina, remarried, Vidal shared a stepfather with Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

He detested his mother (“drunks are not much fun to be around”) and worshiped his grandfather, from whom he inherited his love for politics.

“He was blind, so from the age of 10, I was reading to him. From the congressional record, from American history, poetry,” Vidal said. “He was very good, he was extraordinary, he was my education.”

Unlike his father, Vidal showed no interest in sports and took to writing at age 14, joined the Navy at 17 and published his first novel, the World War II-themed “Williwaw,” while on night watch in port at 19. It was well-received.

But it was his third novel, the coming-out tale “The City and the Pillar,” that brought him notoriety.

The book “got reviews everywhere,” Bram said. “It also got attacked everywhere, and he really ended up getting kicked in the teeth on it. He was only 23 years old, and I don’t think he expected it to be treated as autobiographical, which it wasn’t.”

The novel came out at a time when laws against homosexuality were still on the books in all 48 states. As a result of the controversy, “He backed away from the subject for a while,” said Bram, who teaches English at New York University. Homosexuality “pops up here and there” in his later work, “but never as strongly as in ‘The City and the Pillar.’ “

Opinion: Gore Vidal hates being dead

Though Vidal’s homosexuality was an “open secret,” Bram said, Vidal never claimed to be gay: He argued that the term “homosexual” was “an adjective, not a noun.”

Vidal himself once said of the book, “I sold a million copies and it caused much distress at The New York Times.” The newspaper, along with others, would not review his future work, forcing Vidal, the pariah, to write mysteries under the pseudonym Edgar Box – and to turn to Hollywood.

While not particularly enamored by it, he was good at churning out dramas for television. He took one of them, the science fiction political satire “Visit to a Small Planet,” and successfully adapted it for Broadway. His other stage success came with “The Best Man,” about two presidential contenders.

Following his lucrative TV stint, Vidal returned to writing and produced three widely acclaimed novels that cemented his reputation as an internationally best-selling author: “Julian” (1964), about the Roman emperor who wanted to restore paganism; “Washington, D.C.” (1967), the first of his fictional chronicles of American history; and “Myra Breckinridge” (1968), a satirical treatise on transsexualism.

At the same time, he published prolifically in magazines his critiques on politics, religion and sexuality.

“I would say that since 1945, the United States, which was absolutely the ‘mandate of heaven,’ as Confucius would say, had fallen upon us,” he told CNN in 2007. “The world was ours. … We’d lost it all. So, my war against American imperialism is my largest.”

Obituaries 2012: The lives they’ve lived

Steers, Vidal’s nephew, did not elaborate on funeral arrangements for the author, only saying that the family asks people to donate to the Alzheimer’s Association instead of sending flowers.

Vidal said in the CNN interview that he wanted to be cremated and then have his ashes placed at Rockcreek Cemetery in Washington. The remains of his partner of five decades, Howard Austen, rest there.

Austen died in 2003.

“We share a plot, and I’ll be there,” Vidal said. “And I’ll be looking forward to seeing him.”

What did Vidal or his works mean to you? Please share with us in the comments below.

CNN’s Matt Smith contributed to this report.