Story highlights

"Half-Blood Blues" captures end of jazz age in 1930s Germany in characters' staccato slang

Novel conveys the paranoia leading up to start of World War II and racial tension of the time

As Canadian-born daughter of Ghanaian immigrants, "I grew up between worlds," novelist says

Esi Edugyan says a sense of uprootedness "lies at the heart of this novel"

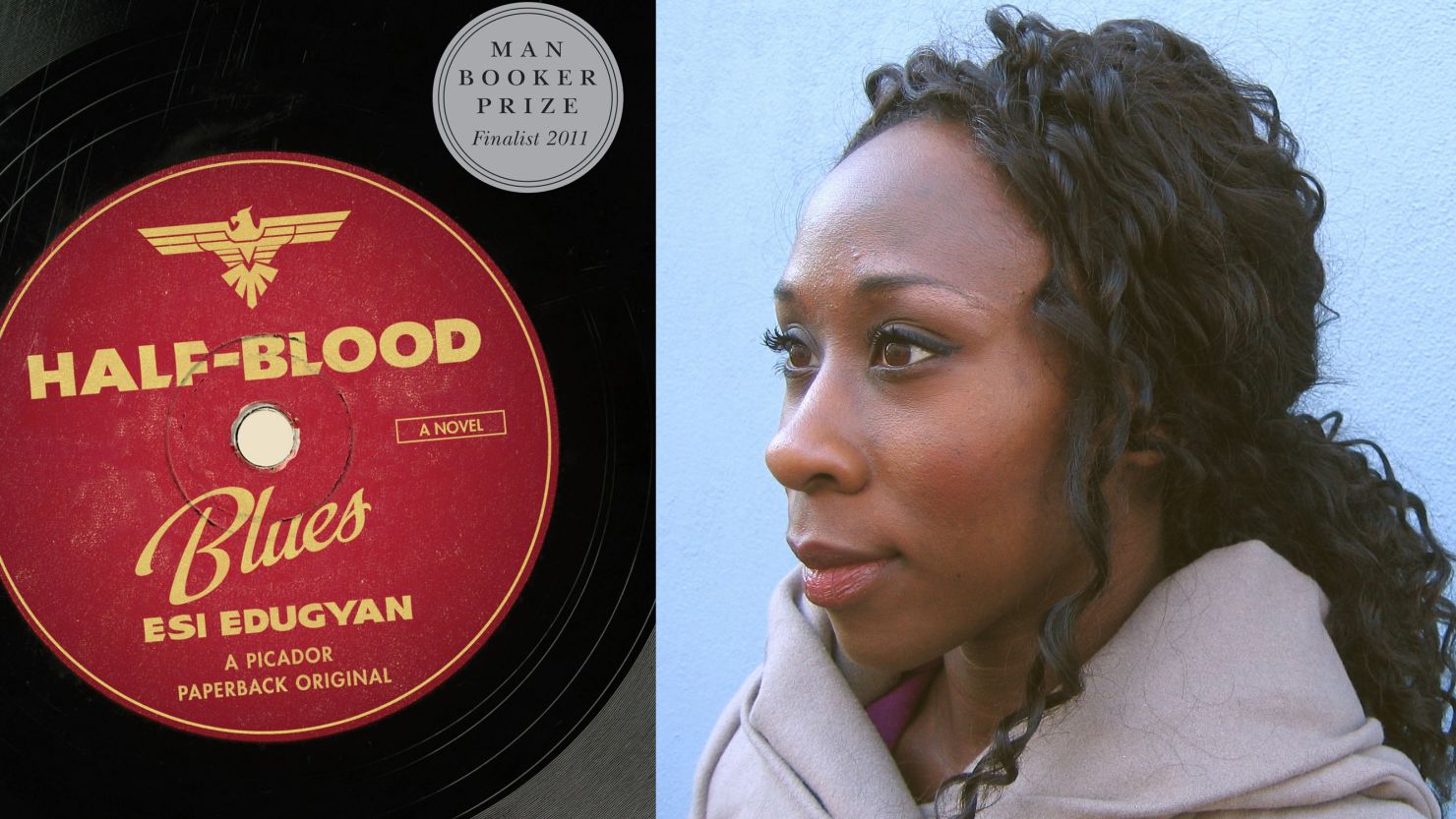

Imagine a smoke-filled jazz club, dark and crowded. The sounds of a trumpet solo echo on stage, while a piano, bass and drums pound out a finger-snapping groove. You can almost smell the cigarette smoke, taste the cheap booze being served. This is Berlin, 1939 – the eve of World War II. These are the Hot Time Swingers, the imagined jazz band at the center of Esi Edugyan’s “Half-Blood Blues.” The novel was a finalist for Britain’s prestigious Man Booker prize in 2011 and reaches U.S. bookstores this week.

The story is told through the eyes of the Swingers’ bass player, Sid Griffiths, in alternating takes between events in Paris and Berlin in 1939 and Baltimore and Berlin in 1992. The novel captures the end of the jazz age in Germany perfectly in the characters’ staccato slang, sounding much like jazz music imagined as dialogue. Offstage, the story captures the paranoia and fear of the days leading up to the start of the war, and the racial tension of the time period.

Sid narrates, but the band’s brilliant young trumpet player, Hieronymus “Hiero” Falk, is the linchpin of the story, a German who happens to be black. Hiero’s prodigy-like talent brings the band success, love and rivalries among its members. After being banned by the Nazis as “degenerate” music, the Swingers escape to Paris, where they meet Louis Armstrong. But then war breaks out, and the Gestapo arrests Hiero in a café. He is never heard from again.

Jump ahead 50 years. Falk has become a cult hero among jazz fans. He’s now the subject of a documentary film. Sid and the only other surviving band member, Chip Jones, are invited to the film’s premiere in Berlin. As they return to celebrate their long-lost friend, Sid, the only witness to Hiero’s disappearance, is forced to reveal a decades-old secret.

“Half-Blood Blues” is the second novel from Edugyan, an author with a bit of a globe-hopping past. She was born and raised in Canada, the daughter of immigrant parents from Ghana. She has studied and lived in the United States and across Europe, including stops in Iceland, Spain and Germany. Now married and mother to an infant daughter, Edugyan lives in Victoria, British Columbia.

CNN recently asked her about the novel in a phone interview and via e-mail. The following is an edited transcript:

CNN: What was the spark behind your book?

Edugyan: I was living in Germany at the time, acutely aware of my difference – being a black woman from Canada. At the same time I’d been reading about the so-called “Rhineland Bastards” – the half-black children of France’s colonial soldiers from Africa stationed in the Rhineland after the close of the first World War. I began imagining their lives in Germany, as both outsiders and insiders, and this naturally led to my wondering what must have happened to them during the 1930s, with the rise of Nazism. This is where my interest in the novel came from. But the book itself more rightly begins with Sid’s voice, his character, the perplexing problems of loyalty and betrayal in any artistic life.

CNN: You really captured the feel, the language and the tone of the late 1930s European jazz scene. Did you research this period extensively before you started writing?

Edugyan: Thank you, that’s kind of you to say. I researched assiduously, both before and during the writing, to capture the feel of that world. But Sid’s voice is so very particular to Sid himself that I would never want it to stand in as some sort of “representative” voice from that time. It’s an approximation of the kind of hybrid language he and his band mates were speaking at the time. But it’s important to remember, too, that Sid is a man straddling two eras – 1930s Europe and 1990s Baltimore – and the shifts in his rhythms, diction, syntax hopefully capture some of that flavor.

CNN: I pictured you listening to a lot of jazz from this time period while you were writing. Did you and were there any jazz artists in particular that inspired you?

Edugyan: It’s interesting to hear you say so. The music was my constant companion, even more than books. Not only as a way to lead me back into the novel after each break but also as a kind of consolation. There was a strength and faith and promise in it that I think I needed at the time. What’s fascinating to me now is to think back on who I was listening to at various points in the novel and read the book with that in mind. Not only the language itself, but the speed and emotion under the prose finds a corollary in the music. Or so it seems to me in retrospect. Among the artists I listened to most often were Sidney Bechet, Bessie Smith and Louis Armstrong.

CNN: Your novel focuses on the Nazi persecution of the Afro-German community. What drew you to this little known chapter of pre-World War II history?

Edugyan: As the Canadian-born daughter of Ghanaian immigrants, I grew up between worlds, in a sense, aware both of my differences and kinships. Loyalties were always mixed, and the world inside the walls of my home was significantly different from the world beyond it.

I did my graduate work at Johns Hopkins, living in Baltimore for a short time, which reinforced this complicated sense of identity. And in the years since, I lived on and off in Europe, where, as ever, I had periods of feeling profoundly at home and periods of total estrangement. I think that sense of uprootedness, that quiet seeking after identity and self, lies at the heart of this novel.

… In the writing itself, you’re not thinking about such things. You just know that there’s a story there, one you want told. And you run with it.

CNN: While Sid narrates the novel, this really felt like Hiero’s story to me. He’s such a compelling character but remains something of an enigma. I assume this was by design?

Edugyan: Absolutely. That unknowability lies at the core of the novel. It seemed it would have been an act of extraordinary presumption to take Hiero’s voice, to speak for him, to fill that silence. And, too, a way of diminishing the sadness of what he (and his real-life counterparts) suffered.

CNN: You come from such an interesting background, the child of Ghanaian émigré parents, born and raised in Canada. You’ve studied in a number of countries, including the U.S. and Europe. You now live in British Columbia. How has all that world travel influenced you as an artist and a person?

Edugyan: … There can be something liberating … for the fiction writer who finds herself caught between worlds. An opportunity to observe and inhabit the skins of others. I know, for myself, that all of that traveling has impacted the kinds of stories I am drawn to.

CNN: You’re also the mother of a young child. Has that changed your approach to writing?

Edugyan: Oh, it’s still so early to tell – our daughter is only 6 months old. But that, too, is turning out to be a different kind of journey.

CNN: What’s next for you?

Edugyan: I find myself staring out the windows an awful lot these days, dreaming up the next book. But our daughter fills up the immediate hours of the day.

Read an excerpt from “Half-Blood Blues.”