Story highlights

Americans may have forgotten a key legacy of Watergate, professors say

Outrage over illegal campaign fundraising led to Watergate reforms

Scholars say these reforms have been erased in this year's election

Editor of Watergate coverage: Big money and secrecy corrupts

A bungled break-in, Deep Throat, a defiant President Richard Nixon declaring, “I am not a crook.”

These are what often come to mind when people hear the word Watergate. But another legacy of the infamous scandal has re-emerged in this year’s presidential race.

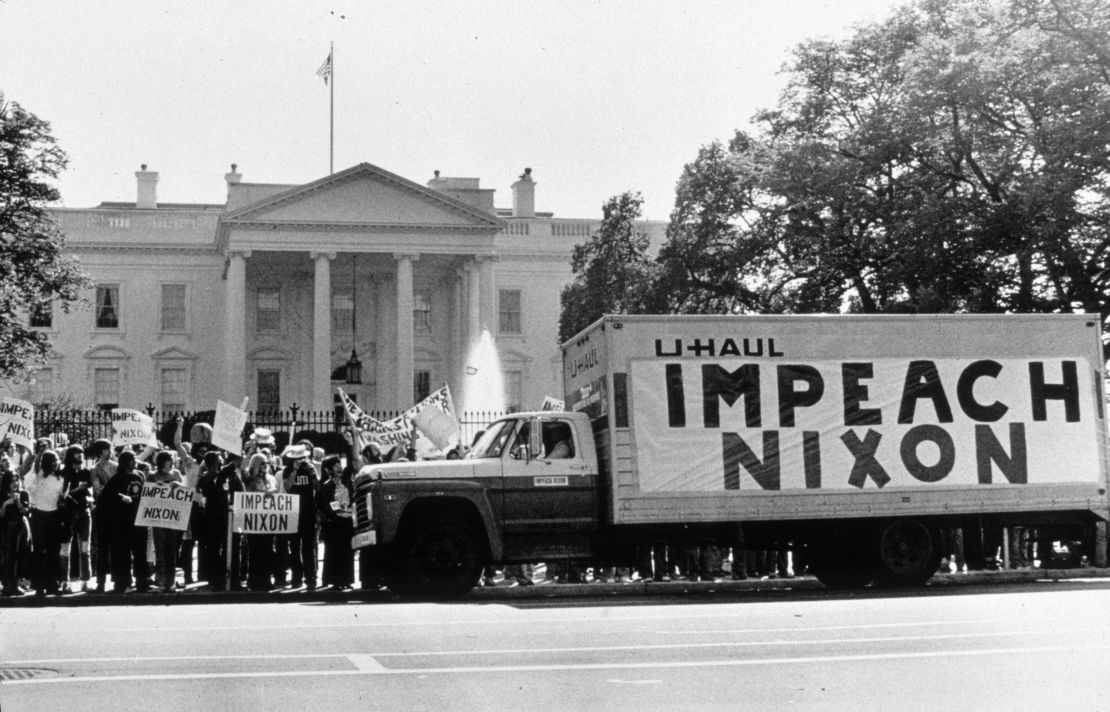

Many Americans may not remember, but public outrage over Watergate led to the enactment of a series of campaign finance reforms designed to restore the country’s faith in government.

While the nation marks the 40th anniversary of the Watergate break-in later this year, some observers say our political leaders have already forgotten a key lesson of Watergate: that anonymous money corrupts political campaigns.

Opinion: It took a scandal to get real campaign finance reform

“Watergate was basically a campaign finance scandal,” says Chris Dolan, a political science professor at Lebanon Valley College in Pennsylvania.

Dolan and others say this historical amnesia can be seen in the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision, which allows corporations and unions to give unlimited campaign donations to so-called super PACs as long as those political action committees are not coordinated with a candidate’s campaign.

Super PACs can quickly pull in huge amounts of money. They have the option of disclosing their donors and donations either semiannually or quarterly in a nonelection year, and quarterly or monthly in an election year.

Critics say super PACs are dangerous because they can delay disclosing details of donations until after elections take place, and they can easily work around restrictions against coordinating with a candidate’s campaign.

“Citizens United will lead to a future that will make Watergate look tame,” Dolan says. “There will be more elections with fewer controls, more spending and great secrecy. The post-Watergate regulations are, in effect, dead.”

Others say the Watergate reforms actually hurt the election process and that the damage can be seen in this year’s presidential race.

The post-Watergate restrictions on campaign fundraising inspired savvy political operators to devise more backdoor ways than ever to steer big money to candidates, says political scientist David Schaefer.

Campaign operators usually stay ahead of campaign reformers, says Schaefer, a professor at the College of the Holy Cross in Massachusetts.

He points to the 2002 McCain-Feingold law as an example. The law set strict limits on contributions to candidates and parties. The result: the rise of “independent” PACs that can receive up to $5,000 from an individual or a national party committee in a calendar year.

PACs often make it easier for a candidate’s supporters to attack their opponents, Schaefer says.

“The candidates cannot be held accountable or responsible for anything PACs say on their behalf, even if there are scurrilous charges that amount to pure mudslinging,” he says.

A slush fund

From the very beginning of Watergate, campaign contributions were intertwined with the scandal.

It began on June 17, 1972, when a security guard called Washington police after discovering white masking tape plastered over a door in a sprawling apartment and office complex known as the Watergate.

Five men in business suits were arrested for breaking into the offices of the Democratic National Committee. Investigators later discovered that one of the burglars had a $25,000 check from President Nixon’s Committee for the Re-election of the President (known as CRP, or CREEP) deposited in his bank account.

Nixon aides had dispatched the burglars to the Democratic headquarters to gather intelligence on his political opponents. To cover up the break-in, the president would take the nation on a two-year series of events that came to be known as Watergate.

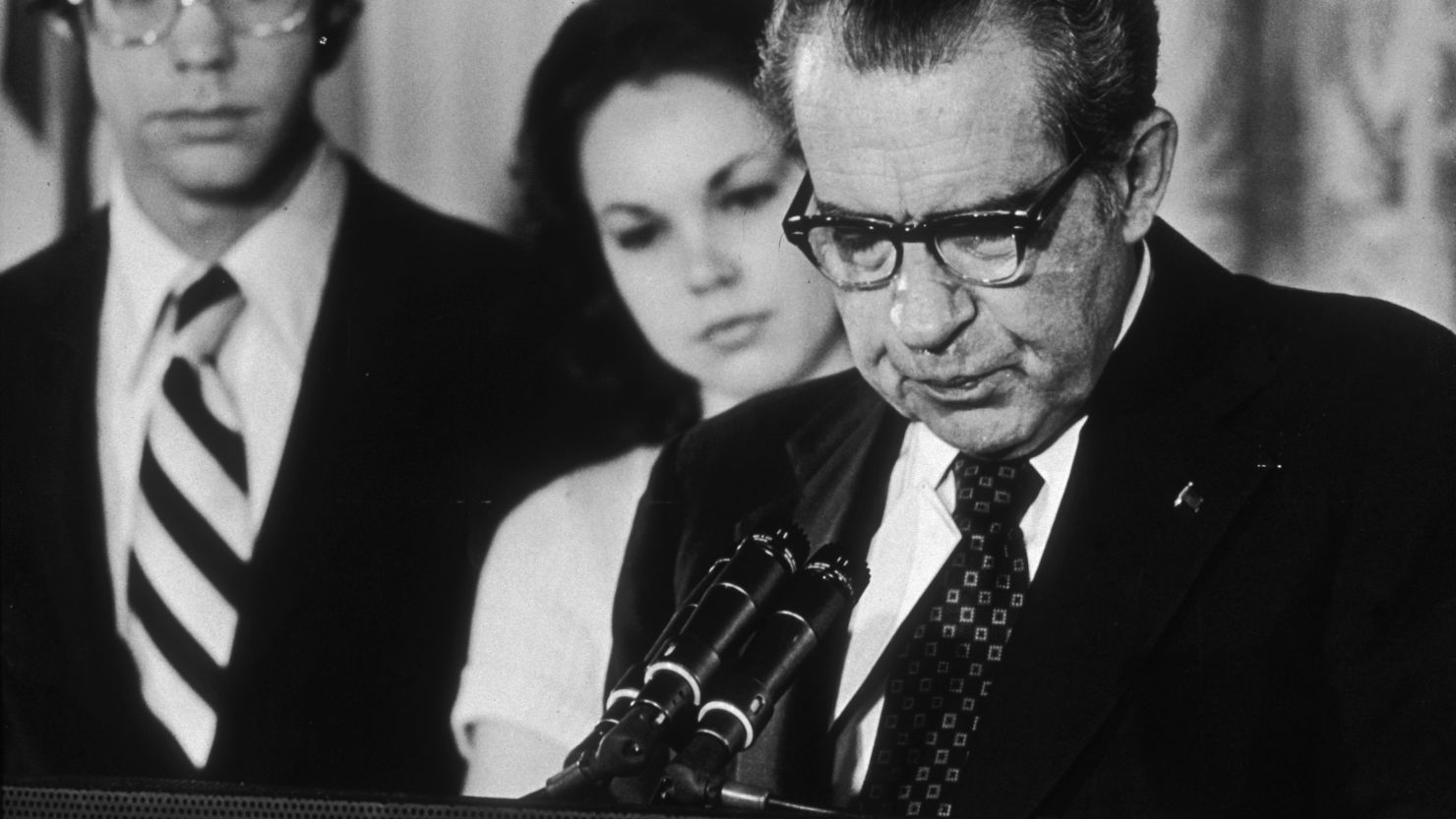

Before resigning in disgrace in 1974, Nixon would order wiretaps for reporters, misuse the Internal Revenue Service, FBI and CIA for political purposes, and prompt a showdown with the Supreme Court. At the end, 30 government officials were convicted, and a disgusted nation began to lose faith in government.

Keeping illegal donations hidden was a prime concern of the Nixon White House after the arrests, says Barry Sussman, a former Washington Post editor who helped lead coverage into the scandal.

Nixon didn’t just cover up a burglary. His re-election campaign chiefs had asked for and received millions in illegal, secret contributions from major American companies.

“They went around with a very heavy hand, telling corporations that we’re going to win and you better get on board. You don’t want to be against us,” says Sussman, author of “The Great Coverup: Nixon and the Scandal of Watergate. “That’s called extortion.”

So much secret money was pouring into the Nixon White House that there were reports of bags of money being delivered to Nixon’s re-election campaign, says Gerry Keim, chairman of the management department at Arizona State University’s business school.

“There was a slush fund,” Keim says. “They were extorting money from corporate interests with the threat of using the IRS to audit them if they didn’t comply.”

Corporations expected something in return, and Nixon delivered. His administration intervened in an antitrust action against one corporation that had given it money and relaxed regulations for a milk company that had done the same.

Congressional investigators who discovered Nixon’s shakedown of corporations decided that the campaign finance system needed to be reformed, says Cornell law professor Robert Hockett.

“There was a widespread public perception that the political process had been thoroughly corrupted,” Hockett says. “Public policy seemed to be up for sale to the highest bidder.”

Why reforms faltered

Congress attempted to change that perception by passing laws that created a system of public financing for political campaigns. Disclosure laws were enacted to root out secret donors. Limits were placed on campaign donations and private expenditures. (A candidate, for example, can’t use campaign money for noncampaign spending.) A bipartisan Federal Election Commission would monitor compliance with the reforms.

Yet those reforms were challenged almost as soon as they were enacted.

In 1976, a divided Supreme Court in Buckley v. Valeo stuck down campaign expenditure limits, equating money with free speech.

Two decades before the Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, the judiciary was already gutting Watergate’s electoral reforms, Hockett says.

“Thanks to Buckley and its progeny, including Citizens United, the post-Watergate electoral reforms have been all but eviscerated,” Hockett says. “We basically have little if anything left in the way of meaningful, democracy-protecting campaign finance regulations.”

Maybe that’s just as well, some political scientists say – that the post-Watergate campaign finance reforms, and others like it, were never destined to last because the flow of money in politics can never be stopped.

Big money and secrecy corrupts?

The best solution for fighting the potentially corrupting influence of big money in politics, they say, is sunlight.

“The real remedy is publicity,” says Schaefer, the Holy Cross professor. “It should be illegal to donate to any political candidate beyond a certain figure – let’s say $1,000 – or even a political action committee without immediately disclosing it on the Internet.”

Transparency, though, isn’t enough when big-money donors are treated like ordinary voters, says former editor Sussman.

“That’s not ‘one man, one vote,’ ” he says. “Corporations can give all they want. Some speech is overwhelming other forms of speech. That’s not democracy.”

Sussman says many people have forgotten one of the most important lessons of Watergate: that big money and secrecy corrupts.

The amount of secret money in this year’s presidential race will dwarf the amount Nixon extorted, he says.

“Nobody would have predicted that these enormous outlays of secret money would now become legal,” he says.

But political scientist Peter Hanson says money is such a dominant force in politics that trying to prevent big-money interests from getting involved is like trying to fight nature.

Attempted reforms of the campaign finance system date further back than Watergate to the Progressive-era reforms of the early 20th century, says Hanson, an assistant professor at the University of Denver.

Demanding transparency in campaign donations may be the most realistic reform possible because it gives voters the information needed to hold candidates accountable, he says.

“Money in politics is like the Mississippi River flowing into the ocean,” Hanson says. “You’re not going to stop the river. You have to direct it in the ways that will best protect public integrity.”