Editor’s Note: This is the first in a weekly series on characteristics of creativity. Next Saturday’s piece will focus on Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jennifer Egan, failure and determination.

Story highlights

Brian Wilson's life illustrative of talent, passion, determination: creative genius

Beach Boys co-founder established "instantly recognizable" sound

Plans and life ran aground after aborted "Smile" project

"Smile Sessions" showcases brilliance; Beach Boys reunion due in 2012

Lives are messy.

Maybe that’s why we try to put them in little boxes with neatly printed labels. Albert Einstein becomes “brilliant physicist.” Ezra Pound is “crazy poet.” Actors, musicians, authors, scientists – all boiled down to a handful of words.

Such has become the case for Brian Wilson. He’s the “troubled musical genius.”

In this sound-bite version of the Beach Boy’s life, there’s “California Girls” and “Good Vibrations” and the “Pet Sounds” album, an invented West Coast soundscape of fast cars, pretty girls and endless summers: Genius.

“What we have from the Beach Boys is such an unmistakable sound that it’s instantly recognizable,” says Paul Levinson, a pop culture professor at Fordham University. “You hear the Beach Boys, and within 10 seconds, you know that it’s them.”

But then there’s the sandbox in the house and the endless days in bed, the substance abuse, flying too high, crashing so fast. “Lying in bed, just like Brian Wilson did,” the Barenaked Ladies sang, and that’s become as defining an image as any.

It’s accurate, but hardly adequate.

Brian Wilson is 69 now. His hair is gray. His belly threatens to peek through the untucked, colorfully striped button-down shirt he’s wearing, a throwback to the Pendleton attire he and his Beach Boys brethren wore in the early ’60s. His shoes, Louis Vuittons with bold “LV” logos stamped on the throatline, look cozy and well-worn.

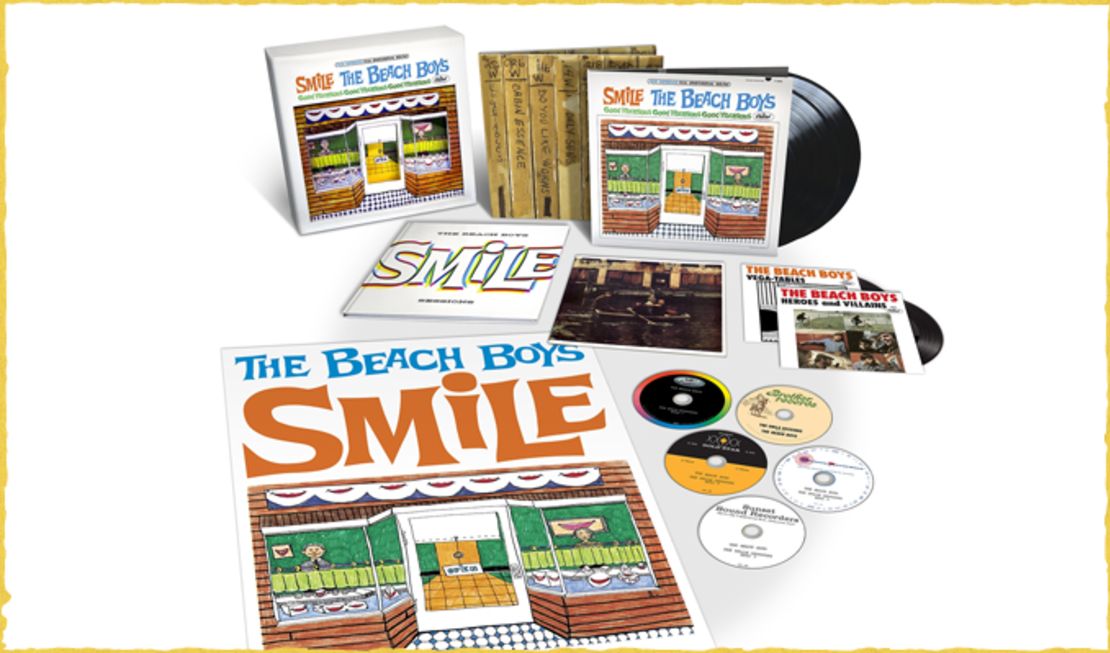

He sits in a suite at the top of the Capitol Records building in Hollywood, surrounded by a makeup artist, an assistant and a public relations manager, all the support necessary for a big-ticket release. In November, the label issued “The Smile Sessions,” a multidisc collection of songs and recordings from the famed Beach Boys album that fell apart in 1967. Portions of it have appeared previously, and Wilson revived the project with his touring band for a well-regarded 2004 album. But the original Beach Boys tapes were more or less shelved for 44 years.

On an L.A.-sunny day in October, Brian is gamely participating in all this music-business showmanship. But you get the feeling he’d be happier in one of the studios downstairs or at home with his wife, children and dogs. Maybe his pensiveness has nothing to do with “Smile” but revisiting the period in which it was recorded can’t help.

“Smile” is the pivot point, in popular lore, between “genius” and “damaged.” The project became engulfed by legend, and you know what they say: When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.

But listen to “The Smile Sessions,” and the sound bite goes away. What’s left is not just a “genius,” but a creative man in full.

For creativity is not just defined by untethered, high-flying talent that flashes like lightning then fades into the darkness. It requires sustainability. It includes, to overlapping degrees, risk taking, genre-mixing skill, an aptitude for improvising and – above all – passion. Experts make a distinction between everyday creativity and big-C Creativity, and Wilson has the latter in spades.

“Big-C creators do not necessarily think differently than the rest of us, but they are more open to new ideas, acquire some degree of domain expertise and are highly motivated to pursue an idea until they have realized its creative potential,” says psychologist and creativity expert Dean Keith Simonton.

You can try to put Brian Wilson in a box. But he won’t stay there. Creativity is too complex for that. It’s all of a piece with him, angelic voices chasing innocence while going through hell.

‘We had to do it’

If there’s a theme that runs through the hours of recordings featured on “The Smile Sessions,” it’s “again.” Over and over, as songs are developed and pieces are recorded, you hear Brian’s voice asking – insisting – for one more take, as he tries to get the music in his head on record.

That passion was apparent from the very beginning of the Beach Boys. At a time when rock ‘n’ roll artists were considered as pliable and disposable as chewing gum, Brian took creative control, producing the Beach Boys – featuring his brothers Carl and Dennis, their cousin Mike Love, and friend Al Jardine – himself. He wrote the songs – sometimes on his own, other times with collaborators – picked the studios and directed the musicians.

He was the “Stalin of the studio,” according to Love.

He drew from his influences and then leapt beyond them, adding a classically inspired opening to “California Girls,” inserting a sharp silence in “The Little Girl I Once Knew,” invoking the deity in “God Only Knows” – all unusual in the Top 40 pop music of the mid-’60s.

It was that kind of drive that led to the “Pet Sounds” album and “Smile,” which combined unusual arrangements, orchestral themes and – in the case of “Smile” – expansive, imagistic lyrics.

“You have to have what I call a ‘persistent obstinacy,’ ” says Julie Burstein, creator of the public radio show “Studio 360” and the author of “Spark: How Creativity Works,” which profiles 35 creative people and partnerships. “It’s a willingness to say, ‘I don’t care what you think. I’m making this happen.’ ”

That’s how the Beach Boys started, Wilson points out. On Labor Day weekend 1961, with the Wilson boys’ parents on vacation, the nascent band blew an emergency fund the couple had left behind on musical instruments and recorded Brian’s song “Surfin’.”

It wasn’t easy to explain to their father, Murry, a mercurial man who often terrorized his sons. “I thought he was going to go, ‘Get in the bathroom, you’re going to get beat with a belt,’ you know, like he usually does,” Brian told CNN’s Larry King in 2004.

But Brian, who had demonstrated an aptitude for music since childhood, defended the choice.

“We had to do it because we wanted to write a song,” he says, his voice taking on the hardness of a determined teenager, as if still addressing his parents.

“Surfin’ ” became a local hit, which led to a contract with Capitol, which led to all the rest. And Brian became a one-man music machine. Until “Smile,” most everything he touched turned to gold records.

Getting to ‘Smile’

By 1966, he’d already picked up the reputation as a genius, thanks to some well-placed hype. Even today, he still doesn’t quite buy it.

“The genius part is being able to make one thing work with another thing, like having the bass play this and the piano play that, or having the lead sing this and the background singers sing that,” he says. “It’s all a matter of balance.”

What Brian had was an ability to combine established forms into something new, the kind of genre-bending that’s a highlight of creativity. The initial Beach Boys sound was a mix of Four Freshmen-style vocal harmonies and Chuck Berry-tough guitar riffs, with a little Phil Spector production thrown in.

With “Pet Sounds” – which included “Wouldn’t It Be Nice,” “God Only Knows” and the revealing lament “I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times” – and “Smile,” Brian expanded the palette to include folk, sound effects and classical elements, including touches of his beloved George Gershwin.

Brian Torff, a jazz musician and music professor at Fairfield University in Connecticut, marvels at the Beach Boy leader’s command.

“[Brian] could take his incredible gift, combine it with a craft – and not many people had that craft in pop music at that time … and could be a mastermind because he knew music so thoroughly,” he says. “The thing that was great about ‘Pet Sounds’ is here was a guy who could craft something that was almost symphonic. Before the Beatles, before ‘Sgt. Pepper’s,’ he was already doing incredible things … really expanding the boundaries of what rock and pop music could be.”

“Pet Sounds,” released in spring 1966, was just the warm-up. The idea for “Smile” essentially began with a new song inspired by his mother’s comment about people giving off “vibrations.” The resulting single was “Good Vibrations.” Brian thought of it “as a smaller, psychedelic version of ‘Rhapsody in Blue,’ ” according to biographer Peter Ames Carlin. It was recorded in four studios, cost a then-unheard-of $50,000 and shot to No. 1 near the end of 1966. Brian called it his “little pocket symphony.”

He planned to do the same thing on a grander scale with “Smile,” his next project. The songs would be built in pieces, like “Good Vibrations,” with elaborate orchestration and recurring motifs. The lyrics would be expansive, telling a story in both word and metaphor. It was going to be as much of a leap from “Pet Sounds” as “Pet Sounds” was from, say, “Fun Fun Fun.”

For Brian, it was “a musical mission, to spread the gospel of love through records,” he writes in the “Smile Sessions” liner notes. He famously called the album a “teenage symphony to God.”

In 1966 pop music, such great plans were not unprecedented. The times were a continuous game of one-upmanship, with artists soaking up ideas from everyone and everywhere. Eventually, even the so-called Establishment took notice: In April 1967, CBS News aired a documentary called “Inside Pop: The Rock Revolution,” hosted by New York Philharmonic conductor Leonard Bernstein, which showcased – among other personalities – Brian Wilson.

It was the kind of hothouse atmosphere conducive to creative advances, as science author Steven Johnson points out: “An idea is not a single thing,” he writes in “Where Good Ideas Come From.” “It is more like a swarm.”

“Smile” started strongly. Brian found a lyricist in Van Dyke Parks, whose fondness for puns and imagery resonated with Brian’s plans for a Technicolor epic steeped in America. The first day they met they wrote “Heroes and Villains,” one of “Smile’s” cornerstones. Other songs quickly followed, including an “Elements” suite – featuring songs referencing air, water, fire and earth – and the gorgeous “Surf’s Up,” with a coda that reached for heavenly transcendence, the aural equivalent of watching a vividly hued sunset from a golden beach.

And then it all fell apart.

‘The yin and the yang’

While reaching for heaven, Brian Wilson was entering hell. It was a place he’d been before.

Though the “tortured artist” has long been a cliché, there does appear to be a relationship between mental illness and creativity. Studies indicate that the brains of highly creative people react differently to information than those of “normal” people.

“Highly creative people are probably highly creative because of certain cognitive mechanisms that also would predispose them to symptoms of mental disorder if they didn’t have additional protective factors,” says Harvard psychology instructor Shelley Carson, author of “Your Creative Mind.”

Their childhoods often “force them to spend time in their inner world. … They can develop their own ideas about things rather than being dependent upon the ideas that are sort of forced down their throat.”

Brian Wilson’s childhood followed that template. Growing up in Hawthorne, California, a working-class suburb of Los Angeles, Brian showed an aptitude for music, constantly listening to “Rhapsody in Blue” and other records, harmonizing with his family. He and Mike Love idolized and emulated the Everly Brothers. Mentors noticed: His high school music instructor was impressed by his grasp of harmony.

And then there was the abuse.

Dad Murry Wilson was afflicted with bouts of depression and easily provoked to rage. Among the brothers, observed Timothy White in his Beach Boys chronicle “The Nearest Faraway Place,” middle son Dennis was the rebellious one, shooting out windows with a BB gun, setting brush fires and cutting class to enjoy the young, mostly unknown pastime of surfing. Carl, the youngest, was generally the peacemaking observer. And Brian, the oldest, was the sensitive soul, something Murry – who’d lost an eye in an industrial accident – took advantage of when in a foul mood.

“Murry would repay Brian’s mild subordinations by removing his artificial eyeball, grabbing a sobbing Brian by the scruff of the neck, and forcing him to peer at the mangled interior of his father’s empty eye socket,” White wrote.

Murry, who managed the band, antagonized many around them.

“His father created lots of problems,” remembers drummer Hal Blaine, a member of the Wrecking Crew, the L.A. studio musicians who frequently recorded the Beach Boys’ instrumental tracks. “His father once had a [song on a] Lawrence Welk record, and he wanted all of Brian’s music to be like he wanted.

“And it finally blew up one day – he told his father, ‘You’re not coming to any more sessions.’ His father was a tough guy, and his attitude was, ‘You guys are never going to amount to anything.’ “

In the “Smile Sessions” press materials, Al Jardine adds, “They were like dynamic opposites – the yin and the yang. There couldn’t be two more opposite people in the world. The failed songwriter and the prodigy.”

Brian was known for occasional eccentricities – he famously built the sandbox in his house in the mid-’60s so he could feel the beach under his feet as he composed – but as he got older, his psychological problems began manifesting themselves acutely. In late 1964, he had to be taken off a plane after having a nervous breakdown. By the time he started working on “Smile,” he had stopped touring and was taking drugs, including hashish, the amphetamine-barbiturate combination Desbutal, and a small amount of LSD. He believed angels were helping him write.

For various reasons, “Smile” started faltering, and Brian’s mind started slipping. At one point, he went to see the Rock Hudson movie “Seconds,” a thriller about a man who adopts a new life. Elements of the movie – including the name of the Hudson character, Wilson – freaked Brian out. And when Brian recorded “Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow,” the “fire” section of the “Elements” suite, he noticed a rash of fires in downtown Los Angeles and believed he was responsible.

Though “Smile” was almost done, the project was abandoned in May 1967.

” ‘Smile,’ ” Brian says in the liner notes, “was killing me.”

Retreat and rebirth

“Smile” could have been the end for Brian Wilson. Having spent months pouring heart and soul into a big project that crashed, it would have been understandable, even at age 24, if he’d channeled his passions elsewhere.

But he didn’t. In creativity, failure is just another word for learning experience. Wilson had taken risks with his music. With the “Smile” chapter ended, he was forced to retrench and find his way anew.

The turnaround didn’t happen quickly. While his bandmates rallied, Wilson went on a well-chronicled descent. This was the era in which he wrote a charming song called “Busy Doin’ Nothin’ ” but also lay in bed for days on end, particularly after his father died in 1973. Brian’s health seesawed for the next 20 years. It wasn’t until the late ’80s that he managed to be rid of his enablers, including a domineering therapist, and recover himself.

The lessons of “Smile” were not forgotten. For one thing, having moved on, Brian kept composing. He still had a passion for music. For another, “Smile” never really went away. Stray songs appeared on Beach Boys records. By the 1980s, the album had been bootlegged enough to stir fans’ blood. In 1993, Capitol released a career-spanning Beach Boys boxed set that included about 30 minutes of the “Smile” tapes.

Wilson initially ignored the clamor – “That was just a bunch of fragments that didn’t even add up to songs,” Brian once said. “I hated it” – but eventually Brian was intrigued enough to listen again to a part of his former life.

So, instead of shoving it away, he incorporated “Smile” into his solo career. The resurrected album was performed live in London in February 2004 and earned a standing ovation. A studio version was released later that year; it won Brian his first Grammy – for “Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow,” of all tracks.

The album proves to be a showcase for Brian’s genre-mixing abilities. He took almost everything he knew about composition, added Parks’ evocative lyrics and created something distinctive and new.

“When you listen to ‘Smile,’ ” says Torff, the Fairfield music professor, “you’ve got everything – you’ve got incredible choral arranging going into doo-wop, there’s a very strong jazz influence on a couple of these, he’s got banjo and harmonica on ‘Cabin Essence,’ which kind of shows a whole country sort of influence, and there’s this rhapsodic Broadway element through the whole thing.

“He’s obviously a guy who has absorbed so many kinds of American music.”

One ‘Smile’ at a time

Sitting in the Capitol Records suite, Brian cradles the fresh-from-the-factory box of “The Smile Sessions.” Along with the CDs, it includes a 60-page book, two vinyl LPs, a collection of photos, even a light switch that illuminates the store pictured on the cover. He perks up at the sight, momentarily slipping into a bright DJ voice. That’s a side of “Smile,” too – humor, something that’s been lost in all the stories around it.

Indeed, from more than four decades on, “Smile” is a window into Brian, then and now.

The newly released “Sessions” features the younger Brian on lead vocals, with a voice not yet ravaged by cigarettes and alcohol. The musicians include the other Wilson brothers, Carl and Dennis, both long dead. But the music, something startling and new for pop then, has become an accepted part of the overall mix in 2011. Brian’s own career reflects that: the former rock ‘n’ roller’s solo albums include nods to Disney standards and Gershwin.

He’s also in a healthier place mentally, even returning to the concert stage in the past couple decades. In fact, putting aside years of enmity, the surviving Beach Boys recently announced they’ll be reuniting for an extensive 50th-anniversary concert tour in 2012, along with a new album.

Painful as it was to put “Smile” aside, perhaps its years in the shadows provided Brian some breathing room to re-establish what it means to be Brian Wilson, accomplished composer, not just Brian Wilson, “troubled genius.”

“The unfinished ‘Smile’ – for all that it was a great part of his legacy – was also an emotional millstone,” says biographer Peter Ames Carlin. “I think it’s been hugely rewarding for him for it to come out and be as richly celebrated as he had always hoped it would be.”

And Brian, whose music once combined influences from his life, is now an influence himself. He’s become part of a creative dialogue: The Beach Boys’ impact is such that the group has become an adjective, the way “Beatlesque” is used to describe a certain kind of catchy pop song. In recent years, R.E.M. (“Near Wild Heaven,” “At My Most Beautiful”), Fountains of Wayne (“The Senator’s Daughter”), Wilco (“Pieholden Suite”) and Sufjan Stevens (the “Illinois” album) have showcased their Beach Boys fixations.

His career has been far from a straight line, of course. He could have stayed with songs about cars ‘n’ girls. He could have given up after “Smile.” He could have succumbed to the madness, the addictions, the enabling. But his passion – his creativity – has carried him through.

He’s ready for the next thing, he says. He and his wife have five adopted children, including two who are younger than 5, and he’s working on new music. He’s inspired. After all he’s gone through, he’s smiling.

“My wife, my family, myself, my collaborators,” he says, pondering his muses. “All of that makes me want to go to the piano and write a song.”