Story highlights

Michigan has the highest student-to-school nurse ratio in the country, at 4,411 to 1

Nurses are handling bigger caseloads as students' medical needs become more complex

Parents should ask who is in charge of their kid's health while at school, expert says

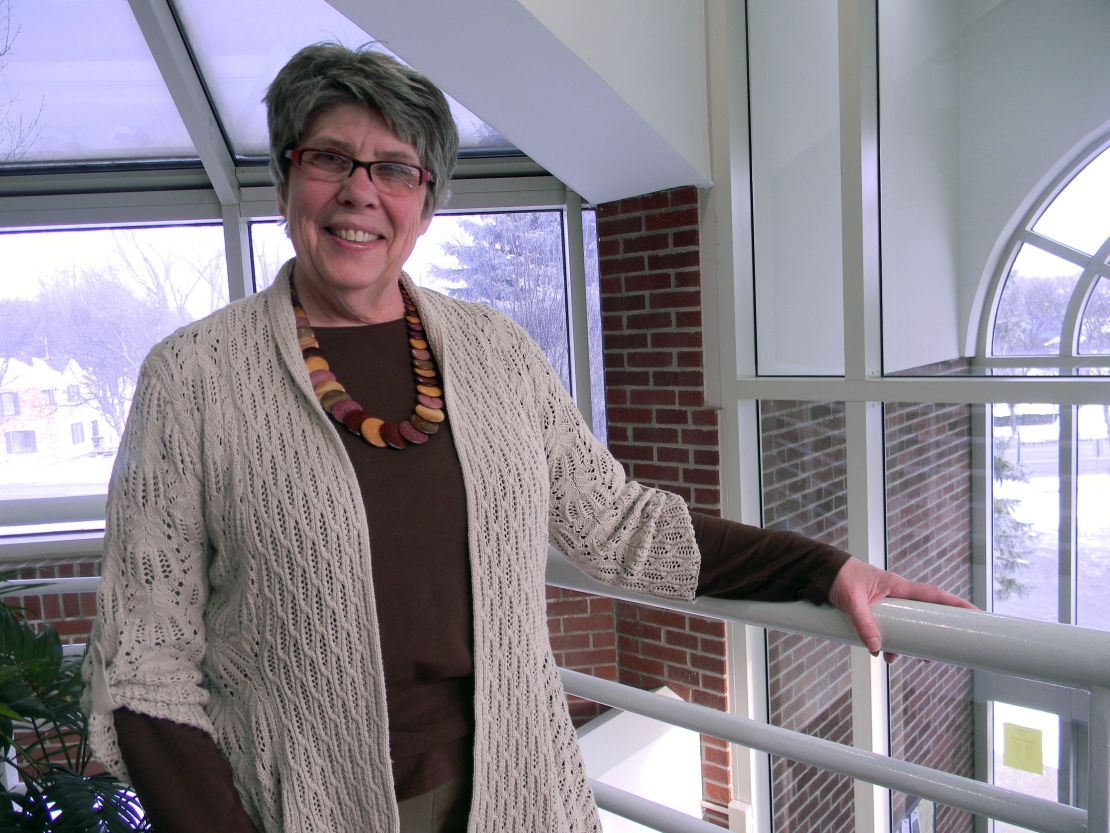

As a school nurse in Rochester, Michigan, Ronda Harrison has more than 15,000 students in 23 buildings under her care. She works out of the district’s administrative offices and spends her days giving PowerPoint presentations to educators and communicating with parents over the phone.

“[It is] scary the fact that I’m responsible for so many schools,” Harrison said. “I miss being ‘Nurse Ronda.’ ”

The 16-year veteran has seen a lot of changes during her career as a nationally certified school nurse, but most notable is the shrinking ranks of her colleagues. Michigan has the highest student-to-school nurse ratio in the country at 4,411 to 1, according to the National Association of School Nurses. Utah isn’t far behind, with a ratio of 3,637 to 1.

This means nurses are handling bigger caseloads, Harrison said, while students’ medical needs are becoming more complex. And educators are now the ones doling out daily medication.

It’s not all bad news, said Linda Davis-Alldritt, president of the National Association of School Nurses. Overall, there has been an increase in funded school nurse positions in the U.S. in the last decade. But the numbers vary significantly by state, and some districts have no school nurses at all.

The bottom line, Davis-Alldritt said, is that the school nurse’s job tends to be at risk during budget cut time.

“The big question for parents to ask when they drop their child off at school is, ‘Who’s going to be taking care of my kid’s health care needs?’ ” Davis-Alldritt said. ” ‘What if my child gets sick? Who’s going to take care of them? What are their qualifications?’ That’s an important question for parents to ask, and the school needs to have the answers.”

It was certainly a question Wendy Rose asked when she and her husband moved their three children to Peoria, Arizona. Their 8-year-old daughter, Adalyne, has type 1 diabetes and celiac disease. The first requires constant monitoring of Adalyne’s blood glucose levels; the second a gluten-free diet.

“Our school nurse has been invaluable,” Rose said. “Insulin is a really tricky hormone – a little in either direction can have drastic results. In reality, it could kill her. I would be very, very nervous sending her to a school environment for a large chunk of her day [with] no one there to monitor her.”

Ever year before school starts, Rose meets with Adalyne’s nurse, a member of the administration and all the educators she will be encountering – from the art teacher to the librarian. A registered nurse herself, Rose had no qualms about putting up fliers around the school with her daughter’s photo that said, “My name is Adalyne. I have diabetes” to alert staff if they noticed her wandering around looking confused because of low blood sugar.

Adalyne is not alone. One in every 400 children has type 1 diabetes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and children are more frequently developing type 2 diabetes, normally an adult disease linked to obesity.

In addition, the prevalence of reported food allergies in children increased 18% between 1997 and 2007. That’s not to mention children with asthma or mental health issues.

Often, the people administering medication in schools are secretaries, principals or teachers. They’re given instructions by parents or the district’s supervising nurse but have little understanding of what the results should be, Davis-Alldritt said.

“Yes, they can give the medication – that’s not really hard,” she said. “But it is really difficult to teach someone how to assess how that medication is working, or how it’s not working.”

Anecdotally, Davis-Alldritt has heard about mistakes made by untrained staff: the child who got ADHD medication twice from a busy principal; the secretary who didn’t know how to properly work an insulin pen and ended up giving none; the child in Washington who died because no one knew to reach for her allergy autoinjector.

She recommends that parents advocate for more school nurses in their district and check in with the staff that handles any health needs.

“Parents have a strong, powerful voice, and they want to make sure their child goes to school and comes home and in the interim is protected and safe.”